|

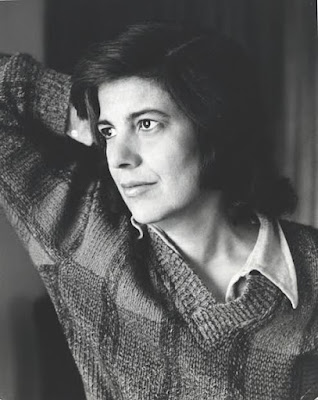

| Susan Sontag |

Godard’s work has been more passionately debated in recent years than that of any other contemporary film-maker. Though he has a good claim to being ranked as the greatest director, aside from Bresson, working actively in the cinema today, it’s still common for intelligent people to be irritated and frustrated by his films, even to find them unbearable. Godard’s films haven’t yet been elevated to the status of classics or masterpieces—as have the best of Eisenstein, Griffith, Gance, Dreyer, Lang, Pabst, Renoir, Vigo, Welles, etc.; or, to take some nearer examples, L’Avventura and Jules and Jim. That is, his films aren’t yet embalmed, immortal, unequivocally (and merely) “beautiful.” They retain their youthful power to offend, to appear “ugly,” irresponsible, frivolous, pretentious, empty. Film-makers and audiences are still learning from Godard’s films, still quarreling with them.

Kauffman included Sontag’s remarks in his review of Godard’s film Weekend:

Weekend (October19, 1968)

By far the best pro-Godard commentary I know is Susan Sontag's essay in the Spring 1968 Partisan Review. I reread it between my two viewings of Weekend. Miss Sontag sketches the adverse criticism of Godard ("What his detractors don't grasp, of course, is that Godard doesn't want to do what they reproach him for not doing"); then she examines these points, attempting to show that the supposed faults are part of Godard's method. Miss Sontag overlooks the fact that some adverse critics assume that Godard works with intention but that intentionality does not itself create an esthetics; still her arguments, all relative to Weekend, are the best critical support for Godard that I can imagine. On the matter of Godard's flashy use of ideas and of literary references:

Certainly ideas are not developed in Godard's films systematically.... They aren't meant to be. In contrast to their role in Brechtian theater, ideas are chiefly formal elements in Godard's films, units of sensory and emotional stimulation.... What's required is that literature indeed undergo its transformation into material, like anything else. This does not exactly contravene the objection by many, including me that Godard is irresponsible in his use of explosive political ideas and callow in his literary display. It says that he is masticating these matters into fodder for cinema; that he treats, say, Mao and Dostoevsky as he would treat a tree, a flower, a kiss. I think this approach is antihistorical, antiintellectual, and finally anticultural, but it does have an imperial bravado. On the ceaseless display of Godardian "effects":

... Godard proposes a new conception of point of view, by staking out the possibility of making films in the first person. By this, I don't mean simply that his films are subjective or personal.... [He] has built up a narrative presence, that of the film-maker, who is the central structural element in the cinematic narrative. This first-person film-maker isn't an actual character in the film.... He is the person responsible for the film who yet stands outside it as a mind beset by more complex, fluctuating concerns than any single film can represent or incarnate.... What he seeks is to conflate the traditional polarities of spontaneous mobile thinking and finished work, of the casual jotting and the fully premeditated statement.

That is a sympathetic description of Godard's effort to make every film a record of his experience in making the film, of the tension he wants to convey between the film and the world, of his frenzied insistent drive to treat film as if it were not a photographic record, fixed before we see it, but something happening at the moment we see it – a response to everything around the film and in Godard at every moment.

What Miss Sontag disregards is that even the Divine Comedy was created by a mind beset by more complex, fluctuating concerns than that poem could incarnate, that Godard's struggle for seeming spontaneity is doomed because no film is a spontaneous event and because the effort to seem spontaneous can get wearisome. With Godard we become aware of the desperation, of the fixed and photographed impromptu.

I cannot summarize all of Miss Sontag's article (it should be read), but, for me, it leads to and away from this sentence:

Just as no absolute, immanent standards can be discovered for determining the composition, duration and place of a shot, there can be no truly sound reason for excluding anything from a film.

This seemingly staggering statement is only the extreme extension of a thesis that any enlightened person would support: there are no absolutes in art. The Godardians take this to mean (like Ivan Karamazov) that therefore everything is permissible. Others of us take it to mean that therefore standards have to be empirically searched out and continually readjusted, to distinguish art from autism; that, just as responsive morals have to be found without a divine authority if humanity is to survive, so responsive esthetics have to be found without canonical standards if art is to survive. The last may be an open question, but it is open as long as men continue to make art.

Stanley Kauffmann, Figures of Light (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), p. 109-111.

No comments:

Post a Comment