Almost as an afterthought I got around to watching the John Hughes film Dutch yesterday. I meant to watch it after watching Planes, Trains and Automobiles on Thanksgiving Day, but it was getting late and I didn’t want to disturb the wonderful mood in which Planes had left me.

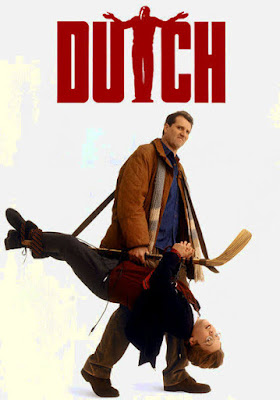

I wanted to see Dutch again because it, too, is a Thanksgiving movie, written and produced by John Hughes. It was directed by Peter Faiman, an Australian best known for Crocodile Dundee (1986). The last film Hughes directed, Curly Sue, was released in October 1991, four months after Dutch. While Curly Sue was a hit, Dutch bombed – largely because of a low key promotion campaign. The only “name” in the cast is Jobeth Williams, who has only three scenes. She plays Natalie Standish, recently divorced from Reed, with whom she shares custody of their son, Doyle. Doyle, who is attending a private boarding school in Georgia, is supposed to spend Thanksgiving with his father. But his father has an important meeting in London, or so he says. When Natalie phones Doyle to break the news that he’s coming to Chicago to be with her instead, he refuses to come.

Natalie: I... I really want you to come home, Doyle.

Doyle: So you can get my approval of your new boyfriend? To appease your guilt?

Natalie: Look, you are old enough to be objective about me and your father and to understand why we're in the situation we're in.

Doyle: Yeah, I know. I understand. You couldn't make it work.

Natalie: If you could see both sides, you'd know that that isn't true. I love you, honey, and...and I want you home.

So Natalie’s boyfriend, Dutch Dooley, volunteers to go to Georgia and drive Doyle to his mother’s house. He tells Natalie, “There's no better way for two guys to get to know each other than to spend a couple of days in a car.”

The film was received with almost unanimous raspberries. Roger Ebert set the tone in his review, complaining that it was formulaic. But he misreads just about everything about the movie. I won’t make great claims for it, but Dutch is actually somewhat less formulaic than Planes, Trains and Automobiles. Dutch exposes something that a film billed as a comedy could barely handle: the pain of a boy abandoned by his father. Ebert complained: “As for young Ethan Randall, he seems smart and capable, but his character is allowed to be too obnoxious for too long, until we finally just get sick of the little worm.”(1) I can understand that Doyle’s pain, expressed so powerfully in direct physical terms (he wants the whole world to feel it), made Ebert squirm. With a father like Reed, the origin of Doyle’s angst isn’t too hard to pinpoint. John Hughes’s father was a salesman, which meant that his family were always moving: “I was kind of quiet,” Hughes told an interviewer. “And every time we would get established somewhere, we would move. Life just started to get good in seventh grade, and then we moved to Chicago.”(2) This admission doesn’t betray what could’ve inspired Doyle’s rage, except that Hughes had a lonely childhood. Doyle simply channels his loneliness into aggression.

There is a quiet scene in which Doyle practices karate in an empty gym. Another boy, whose father works as the school janitor, enters to tell him that he’s invited to eat Thanksgiving dinner with his family.

Schoolboy: My parents wanted to know if, since you're not going home, you'd wanna come over to our house for Thanksgiving.

Doyle: Don't think I could handle that much fun.

Boy: Is that a no?

Doyle: That's a no.

Boy: Great. Have a nice weekend rotting in your own pissed-off world.

Doyle shadow punches the air savagely. When Dutch arrives and tells Doyle he’s there to drive him home:

Dutch: I told your mother I'd take you home for the holidays.

Doyle: I have plans.

Dutch: Stay here? You gonna watch the football game, make a turkey sandwich and hang yourself in the toilet?

Doyle: I said I have plans. Leave it at that. Now please go.

John Hughes had never gone near the subject of divorce except in the script for Dutch. If he was going to treat the subject at all, he seemed determined to explore its hardest impact on a child of divorced parents. The acts of cruelty (there is really no other word for it) that Dutch and Doyle inflict upon each other on their extended journey to Natalie’s home are supposed to be funny, but when the viewer puts himself in the place of either of the antagonists, they are sometimes painful to watch. Doyle karate kicks Dutch in the balls and even knocks him out when Dutch tells him to hit him with his best shot. In return, Dutch abandons Doyle on the road and he has to walk miles through the snow to the motel. Then Doyle parks Dutch’s car in the middle of the road so a semi truck can smash into it. These two adversaries turn out to be more equally matched than either would admit. They wind up hitchhiking instead of letting Natalie find out that either of them has failed. Finally, having to sleep at a mission flop house, Doyle meets a woman whose husband lost his job. But they have a car, and after Dutch promises the husband a job at his construction company, they give them a ride the rest of the way to Natalie’s house.

Dutch is a smaller, lesser effort than Hughes’s other Thanksgiving movie, Planes, Trains and Automobiles. I found Dutch to be more strange, deeper than the earlier film. Much less funny, but more real. Doyle’s private school was shot at Berry College in Rome, Georgia at the height of Autumn. There is one shot in which a lonely Doyle walks defiantly through a field of dead leaves, kicking and stomping on them. There isn’t another soul in the shot, as if everyone had already gone home for the holidays but Doyle. Ethan Randall (later Ethan Embry) plays Doyle. He was 12 during shooting, and while his transformation into a loving son at the film’s conclusion is handled too neatly, his performance is balanced by Ed O’Neill as Dutch. He is grotesque. Even if his role is almost completely unsympathetic, he is convincing as a roughneck, hard-headed “working class clod” (Doyle’s words). But he is defeated by Doyle. His defeat reminded me of the beautiful Alexander Mackendrick film The Maggie, in which a wealthy American tries to wrest a boatload of his household goods from the Scots crew of a “puffer” – a small ship sailing the lochs and firths of the Scottish highlands. He, too, gives up at the end of the film. But Doyle persuades Dutch not to give up, and together they make it the rest of the way home.

P. J. O’Rourke, who was a friend of John Hughes, spoke of his reverence for family: “Family was the most conservative thing about John. Walking across the family room in your stocking feet and stepping on a Lego (ouch!) was the fundamental building block of society.”(3) Even a family as splintered as Doyle’s is the only source of love and salvation for him.

On a personal note, I once found myself stranded at a Catholic “Home for Boys” (read: orphanage) over the holidays in 1966. This, despite the fact that I had parents, neither of whom seemed to know what to do with me. The home, coincidentally, was also in Georgia. The only difference was that I was stranded there with my older brother. I was 8, and the experience affected him a great deal more. We were invited by a local family to eat Thanksgiving dinner in their home. It stands out in my memory because the family had a horse and I was allowed to sit in the saddle and ride it for the first time in my life.

(1) "Dutch," Chicago Sun-Times, July 17, 1991.

(2) "Molly Ringwald Interviews John Hughes". Seventeen Magazine, Spring 1986.

(3) ”Don't You Forget About Me: The John Hughes I Knew” The Daily Beast, March 22, 2015.