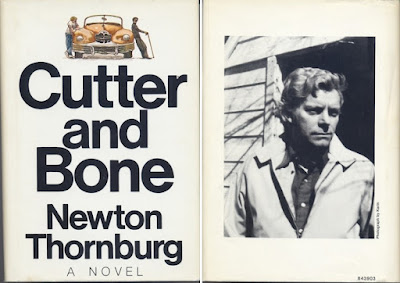

Quite the oddest thing about reading the novel, Cutter and Bone by Newton Thornburg, was wishing that it were more faithful to the movie. The novel sprawls not just up and down the California coast, but after what comes as the novel's climax, the action plunges halfway across America to Missouri. In the movie (that I reviewed here two years ago), everything happens in and around a beautifully evoked Santa Barbara, redubbed Santa Condominica by Alex Cutter.

Thornburg (1929-2011) was a successful novelist who specialized in low-grade psychological thrillers and whose style was sometimes compared to Ross MacDonald. Cutter and Bone was his fourth novel, published in 1976, and is often cited as his best work. Set in Santa Barbara, nestled between hills and the Pacific Ocean, it is redolent of the 1970s post-Vietnam War bad faith that gripped America after it lost the war and then pivoted into amnesia, burying the subject of military and political failure under another burst of the usual trippy consumerism. The titular characters are Alex Cutter, a Vietnam veteran disfigured in the war, missing half a leg, half an arm and one eye, and Richard Bone, a kind of beach bum adonis who crashes at Cutter’s house and occasionally provides sexual services to middle-aged women visiting Santa Barbara. Alex is married to a woman named Maureen, whom he calls Mo, and they have an infant son, Alex III (or is it IV?). Another reason why Bone sticks around Cutter’s house is because he’s in love with Mo.

One night Bone’s jalopy 1948 MG breaks down and, after abandoning it, electing to walk the rest of the way to a bar where Cutter is holding court, he sees “a late-model car” pull into an alley, a man get out and pull what could have been a bag of golf clubs out of the passenger seat and throws it into an adjacent dumpster, and drive quickly away. The next day some cops show up at Cutter’s house looking for Bone, having found his MG parked near the scene of a crime: the golf clubs turned out to be the dead body of a 17-year-old cheerleader. In the dark, Bone couldn’t make out the man’s appearance, and tells the police as much, but reading the local newspaper later in the day, he sees a photograph of J. J. Wolfe, a corporate magnate, and says, “My god, it’s him.”

Thereafter, the novel turns into a caper involving Cutter, Bone, and the murder victim’s older sister, Valerie, to blackmail J. J. Wolfe. Cutter tells Bone the reason why he wants to do it:

I get out of bed every day like it was Armageddon. I can’t stand the thought of looking at faces and listening to voices. I can’t stand communicating. I’d rather kiss Mo’s clit than her mouth. I’d rather bounce a ball than the goddamn kid. I don’t want to read anymore, I don’t want to see movies, I don’t want to sit here and look at the goddamn sea. Because it all makes me want to puke, Rich. It gives me the shakes. I guess the word is despair. And it’s become like my heart. I mean it pumps day and night, steady. I’m never without it. I’m sick all the time. So I think about death. I think I would as soon be dead.

But there’s another reason Cutter wants to nail J. J. Wolfe:

I don’t like this motherfucker Wolfe and all the motherfuckers like him, all the movers and shakers of this world, kiddo, because I saw them too many times, and I saw the people they moved and shook. I saw the soft white motherfuckers in their civvies and flak jackets come slicking in from Long Binh to look us over out in the boonies, see that everything was going sweet and smooth, the killing and the cutting and the sewing up, and then they’d grunt and fart and squeeze their way back into their choppers and slick on back to Washington or Wall Street or Peoria and say on with the show, America, a few more bombs will do it, a few more arms and legs. And I don’t care if they were as smooth as the Bundys or as cornpone as Senator Eastland or this cat Wolfe, one fact was always the same, is always the same—it’s never their ass they lay on the line, man, never theirs, but ours, mine.

In a 1981 interview, Thornburg stated:

"You had to know Cutter, almost live with him, to understand the savagery of his despair, that it precluded his responding to any idea or situation with anything except laughter, sometimes wild but more often oblique and cunning, as now. His mind was a house of mirrors, distortion reflecting distortion."

Bone agrees to help him blackmail Wolfe only after lengthy consideration. The caper doesn’t turn out well for either of them.

I got around to reading Cutter and Bone last month. Because of its reputation, I was curious to discover how it differed from the movie, called Cutter’s Way. I was disappointed to find Thornburg as a novelist a few rungs below Raymond Chandler and a few more below James M. Cain. He goes to some lengths showing off his knowledge of – or research on – Santa Barbara, dropping the names some of its streets and landmarks. I looked them up on Google Maps and while they gave the story a strong sense of the locale, they didn't make the characters and action enacted thereagainst by Thornburg any more convincing. In fact, they only emphasized their insubstantiality.

Cutter’s Way was an uneven but quite distractingly alive film with three fine performances from its principals, Jeff Bridges, John Heard, and Lisa Eichorn. There are some small and some quite large differences, the most surprising of which is the film’s overall superiority to the book.

In the movie, I got the impression that "Bone" was Richard’s nickname, since he moonlighted as a hustler, a dependable boner; Alex and Mo don’t have a child; J. J. Wolfe becomes J. J. Cord; and instead of Ibiza as Cutter’s dream destination, it’s Tahiti. In fact, the best line in the movie, spoken by Cutter to Mo, is “Some day in Tahiti we’ll look on all this and laugh.”

Tasked with deriving a film script from the novel, Jeffrey Alan Fiskin admitted its faults: "The set-up's great, the characters are fine. But the last half of the book is an instant replay of Easy Rider. You cannot make a film out of this." That Fiskin managed to make a good film out of Cutter and Bone, with Ivan Passer as director, attests to the importance of being unfaithful to the original text.

The resolution of Cutter’s Way unfolds in Santa Barbara, but the novel crosses the country in Cutter’s 1948 Packard Clipper in pursuit of J. J. Wolfe to his cattle ranch in Missouri. Once there, the escapade quickly becomes as grotesque as Andy Kaufman’s foray into pro wrestling, deliberately mocking its fans by showing them soap and toilet paper, and telling them, “I’m from Hollywood!” Thornburg had raised cattle on a sixty-acre ranch in the Jane, Missouri, but he indulges in some of the worst redneck portraiture. His ending is practically copied from the 1969 movie Easy Rider, except that Bone is alone and driving Cutter’s Packard.

The film, in complete contrast, ends in a bold, astonishing flourish of action and violence that left me speechless the first time I watched it.