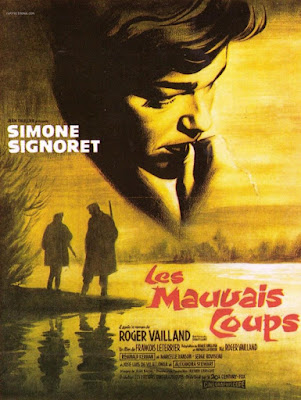

In an essay published in The Hudson Review in 1965, “Some Obiter Dicta on Recent French Films,” Vernon Young singled out four films for scrutiny: Claude Lelouch’s L’Amour Avec des si (he misidentified it Avec des si), Jacques Démy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Truffaut’s La Peau Douce, and Les Mauvais Coups. Only his last choice required explanation:

“My justification for introducing a five-year-old film is my belief that among the critic’s obligations is the salvaging of neglected films before they go softly into that dark night, a fate that appears to be overtaking François Leterrier’s Les Mauvais Coups.”

Let’s just say that Leterrier’s film, despite Young’s valiant effort, was overtaken. The reason, Young pointed out, was probably because, at the time of its release, it wasn’t recognizably a product of the New Wave:

"What should seem obvious to any filmgoer who is old enough to have a memory is that the similarities between the generation of filmmakers in France and the preceding ones are more numerous than the discrepancies. However exuberant, experimental, informal, or even disorderly the new contingent has insisted on being, with whatever degree of seriousness its members have tried out audacities of narration and cutting, it has been working, for the most part, in what might be called the classical tradition of French cinema. . . . I want to illustrate the range and the rich interdependence of French film-making with four films."

Sixty-one years later, I finally found Les Mauvais Coups, and I am pleased to announce that I wasn’t disappointed. The title is practically untranslatable. The Bad Knocks is a close approximation, but it doesn't work for a title, any more than The 400 Blows did. It's set in an especially soggy and bleak autumn, and the emotions on display are especially raw. But there is also an undressed Alexandra Stewart and a thinly disguised lesbian undercurrent; so an American distributor called it Naked Autumn and it had the usual limited release to arthouse cinemas across the U.S.

As it happens, Naked Autumn is not a half-bad title. It captures the visual tone of the film, a quite unpicturesque setting – the eastern French department of Jura, near the Swiss border, a region of lakes and vineyards which, in September, gives way all too readily to autumnal gloom. A couple married for ten years, Milan and Roberte, live in a chateau with one servant, Radiguette, who cooks for them. Milan has retired from race car driving and appears to respond to living in a quiet nowhere better than Roberte, who has settled into a routine of alcohol consumption.

After a panoramic introduction under the opening credits to a landscape of gnarled tree limbs against an antelucan sky, accompanied by discordant piano chords, we are set down at an old chateau (probably a tourist hotel by now) in which an alarm clock rings. A man, Milan, wakes, snuffs the alarm and turns on the lamp. He tries to rouse Roberte lying beside him but gets only a grumbling “leave me alone” out of her. He manages to get her attention with a few shots of the hair of the dog. They’re up early to go duck shooting.

They arrive at a predetermined spot outdoors just as the sun is rising. Milan tells Roberte to watch as the morning mist lifts. “I always love that,” he says. “It’s like a girl undressing.“ He bags a jay. “A male,” he tells Roberte. “The female will be lonely,” she says. Milan is in his element. But Roberte, played by Simone Signoret as if her career were on the line, isn’t up for something so wholesome. A strong undercurrent of discontent is revealed between them. She reminds him of an infidelity and he tells her of a recurring dream of her with another man.

Back in the chateau, Milan works on writing his reminiscences of Le Mans, ostensibly the reason they’ve come to live in such a remote place. Their pastime seems to be mutual torment – her jealousy versus his now jaded faithfulness. Hélène, an attractive young school teacher arrives in the village, and both Milan and Roberte see potential in her. He notices her youthful confidence, she sees in her a rival. Hélène is played by the Canadian actress Alexandra Stewart, who would soon become a siren of French cinema. (I will never forget her as Alain’s final, unobtainable love object Solange in Louis Malle’s Le Feu Follet.)

Reginald Kernan plays Milan. He was born in Savannah, Georgia in 1914 and died in Savannah, Georgia in 1983. In between he had been a doctor, a model, and an actor in four French films. Les Mauvais Coups was the first and by far the best. He is exceptionally tall, which makes him a very unlikely race car driver, but he has a distinguished face and bearing.

But then there is Signoret. She is fantastic. When she is in the shot she devours everything – the décor, the other actors – even the fetching Alexandra. Signoret plays a woman desperately clutching to the last remaining straws that make her feel alive – an obstinate man who gave up his only passion when a friend was killed in a racing accident. She allows Milan an occasional fling as long as he comes back to her when it’s over. What she doesn’t see – until he makes her see it – is that it’s over for her as well.

In the small role of Luigi, Milan’s racing manager, it was marvelous to see Marcello Pagliero again. He played the Italian resistance leader tortured by Nazis in Rossellini’s Open City.

Jean Badal, the cinematographer, contributes beautifully fluid black-and-white imagery of an uninspiring locality. The music supplied by Maurice Leroux is subtly atonal. It always strikes me that, while such music scrupulously avoids being programmatic, it’s used so often in films to evoke discord and darkness. Here it fits quite unobtrusively.

I found Les Mauvais Coups to be better than most of Chabrol – not as cool, but more musical, less mannered, without "indications" pointing toward a bigger design. The trouble with genre movies is that they’re weighed down, forced into a pre-existing framework. Chabrol’s best films transcend genres, but they still keep one foot in genre. François Leterrier, who was discovered for the lead role in Bresson's A Man Escaped, wasn’t trying to make any personal statement or invent a new style. He wasn’t trying to shock or surprise the viewer. He was using all of his skills to realize a thankless tale of loveless love. The marriage depicted in the film is somewhat familiar to a divorcée like me. Returning to Vernon Young, he sums up the reason why Milan resists the love of Hélène:

Long servitude to a lethal woman burns too much heart out of a man for him to believe he has enough left to risk on another.

No comments:

Post a Comment