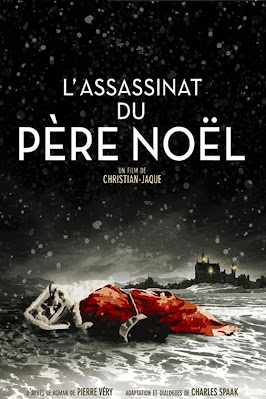

You wouldn’t know it from the title, but Who Killed Santa Claus? is a lovely little Christmas fable whose artifice is less than perfect, but artful all the same.

Firstly, just as the French traditions of what they call Noël are only vaguely

paralleled by our grossly impure American traditions of Christmas, the title of

the Christian-Jaque film L’Assasinat du Père

Noël

isn’t quite what English-speaking filmgoers got when they watched Who Killed

Santa Claus? Père Noël (an old

artisan played by the great Harry Baur) goes house to house on Christmas Eve to

have a drink and lecture children about how well or badly they behaved during

the year. Children even stay awake to be in his presence, instead of pretending

to be asleep. But the village in the film is a poor one, whose families can

barely afford the smallest toy for their children.

Secondly, quite apart from its qualities as a film, Who Killed Santa Claus? is reputedly one of those “encoded” films made during the German Occupation of France (1940-1944) whose subtext has something to do, presumably, with who betrayed France in June 1940. Marcel Carné’s Les Visiteurs du Soir is another, but that film is marvelous without having to bother about any clandestine messages.

Shot in a snowbound

village in the French Alps, L’Assasinat du Père Noël places us among people effectively

cut off from a world beyond the mountain peaks where, in the abundant exterior

shots, even the use of filters that can turn day into night (a technique the

French call “la nuit Americain,”), it’s sometimes hard to tell them apart.

The cast includes

a few faces familiar to an avid fan of French cinema, like Robert Le Vigan, who

played the suicidal painter in Quai des brumes, Fernand Ledoux, who played the

cuckolded husband in Renoir’s La Bête humaine, and Bernard Blier appears late

in the film as a gendarme.

But the film

belongs to Harry Baur, who had become one of the finest and most beloved actors

in French cinema by the time he appeared here as the globe maker, Gaspard Cornusse, and he invests the role with an

imposing weight. Cornusse is a world traveler who tells everyone who cares to

listen stories of all the places, especially China, he has visited. His tales inspire

Roland de La Faille, the local Baron, to

leave the village and travel to the four corners of the earth searching for something

he can neither find nor define. On his return to the village, Roland blames old

Cornusse for encouraging him to become a wanderer, and of ruining himself in

his wanderings. Cornusse’s daughter, Catherine, seems to live in some kind of

trance, like la belle au bois dormant. When she learns that Roland has returned

to the village, she awakes and announces that she has always loved him since

she first saw him ride down the village Street on a white horse.

But a sinister

figure intrudes on the placid town on Christmas Eve when the church’s old

priest places a priceless relic of Saint Nicholas, a diamond, on a star above

the Nativity scene. The gem is stolen during the Christmas service when Léon Villard, the village schoolmaster (and intellectual ass) stages an explosive

demonstration outside the church (on behalf of atheism!). Witnesses say they

saw old Cornusse near the Nativity scene, in his full Santa disguise. But when

Santa is found dead in the snow, and is unmasked as a (dead) stranger, the

clues point at Cornusse himself.

Charles Spaak,

whose credits include the classics Le Grand Jeu, La Kermesse Heroique, and La

Grande Illusion, adapted the film’s script from the Pierre Very novel. Much of

the film’s length is taken up with the dropping of clues to solve the double

mystery, but they are – thankfully – inconsequential because so much is going

on in the film. But it all ends sweetly with Santa giving a secret gift to a

sick child as no one other than Dickens could have brought off successfully.

Christian-Jaque –

who later married Martine Carol, Lola Montes herself – proved, with his earlier

film Les Disparus de Saint-Agil, to be one of those filmmakers who know how to

direct children, and he does beautifully again here. Armand Thirard’s photography,

which included working in what must have been difficult conditions high in the

Alps where snow is piled three feet deep on rooftops and paths through the snow

are constantly having to be cleared, provides beautiful shadow effects on the snow.

Watching Cornusse in his Santa costume struggle from house to house – and drink

to drink – is entertaining in itself.

L’Assasinat du Père

Noël is an altogether surprising, but strange film. It was restored by Pathe in

2015 and its rediscovery is another droll chapter of the process of film

restoration that will perhaps never end. It originally premiered in Paris on October 16,

1941. It was the first film produced by the German-owned Continental Films.

Shortly thereafter, Harry Baur was accused by the collaborationist newspaper Je

suis partout of being a Jew. According to Roberto Chiesi

in his tribute to Baur, “[he] fended for himself and went to Germany to shoot a

film, but in May of 1942 he was arrested and tortured for four months by the

Gestapo. The experience reduced him to a shadow of his former self, and he died

on April 8, 1943.”(1)

Whatever coded messages are hidden in L’Assasinat

du Père Noël will have to wait for scholars

to decode. For now, it is well worth the wait to see at Christmas.

(1) The tribute is located here.

No comments:

Post a Comment