Why is it that Tolstoy’s grasp seems to be so much larger than Dickens’s – why is it that he seems able to tell you so much more about yourself? It is because he is writing about people who are growing. In my own mind Dickens’s people are present far more often and far more vividly than Tolstoy’s, but always in a single unchangeable attitude, like pictures or pieces of furniture. You cannot hold an imaginary conversation with a Dickens character as you can with, say, Peter [sic] Bezukhov. It is because Dickens’s characters have no mental life. (1)

By the time the nine-hour Trevor Nunn production of The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby was broadcast on American TV over four consecutive evenings in January 1983, I had already seen Alberto Cavalcanti’s film version of the Dickens novel. For anyone who, like me, is unused to watching any kind of theater, the Nunn production was a revelation. For John Simon, experienced New York theater critic, who saw the production when it played on Broadway, it forced from him qualified praise:

The typical Dickens novel has three layers. There is the plot, which in the early works tends to be a fairy tale. Good people, mostly young, struggle, are set upon by evil wizards and witches, but, partly through their own efforts and partly through the help of good fairies, end up triumphant, while the wicked tormentors get their just desserts. Wilde may have been thinking of Dickens when he made Miss Prism say about her three-volume novel, “the good ended happily, the bad unhappily. That is what fiction means.” Over this fairy-tale layer stretches a layer of description: people in their settings, customs, and manners; the look and feel of a place and period. This is what Walter Bagehot appreciated about Dickens: “He describes London like a special correspondent for posterity.” The third layer is the social commentary: the author’s noble philippics against every iniquity, whether caused by political systems or human nature.

Now a stage version of Nicholas Nickleby, even one that lasts eight and a half hours, as does the one adapted by David Edgar for the Royal Shakespeare Company, can do scant justice to the second and third layers because, except in very small doses – they don’t “play.” That leaves the fairy-tale plot, which the stage, with some abridgement, can render beautifully. And since Dickens’s imagination is matchless, an uncommon wealth of characters pours, hurtles, slithers, skulks, and trips across the stage in a veritable Dance of Life.

Where the play errs, Simon points out, is in “the dramatization of Smike…. In the novel, Smike is a somewhat mentally deficient youth with a limp, but otherwise lean and tall, very good at household and garden tasks, and speaking plainly and coherently. In the play, he becomes a ghastly victim of something like cerebral palsy – disfigured, brain-damaged, deformed in body and limbs – a junior-version Elephant Man.”(2)

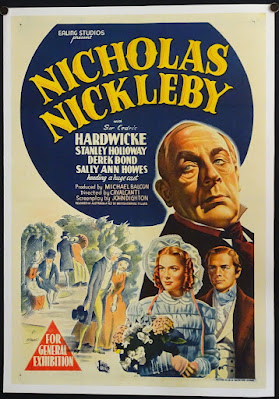

I have never agreed with the argument that Dickens has been served well by his film adaptations. Aside from the many Christmas Carols, which stand or fall with the actor playing Ebenezer Scrooge, I can think of only two successful films based on Dickens novels. Coincidentally, both films were released by the Rank Organization: Alberto Cavalcanti’s The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby in 1947 and David Lean’s Oliver Twist in 1948. Because of the release of Lean’s far less effective but much bigger-budgeted Great Expectations the day after Christmas in 1946 (seriously handicapped by the miscasting of Valerie Hobson as Estella), Cavalcanti’s Nicholas Nickleby was underpublicized and overshadowed on its release the following March. It has been nearly forgotten since then.

Unlike a theatrical adaptation of a Dickens novel, a film can do more than just transpose the plot. It can, with its design, costumes, and camera movements, recreate the settings to a degree of accuracy impossible on the stage. It can show us a selection of locations of what was once a completely fictional world, and give us a much more intimate understanding of the characters’ relations to that world. In other words, film has the almost uncanny ability to represent life – even when it is a product of pure invention.

During the war Alberto Cavalcanti worked on the script for a film adaptation of Nicholas Nickleby, but shooting was postponed when Derek Bond, his lead actor, was called up for military service. When the war was over, Cavalcanti wanted to make a multi-episode film about Dickens called The Green Chair, but Michael Balcon, his producer at Ealing, proposed that he go through with Nicholas Nickleby.

Seeing it again after more than forty years, the strong impression that it gives me is that of classical perfection. Though the film was released in 1947, it seems, strangely, older. David Lean could take the emotional side of Dickens and give it fuller breath, but Cavalcanti reminds us that Dickens was closer to Balzac than Flaubert. The pre-Victorian Dickens world is a populated, almost overpopulated world, and Cavalvanti, while having to cut the novel savagely just to make a 103 minute film of it, yet preserves the setting of the tale, the world of 1830.

The film had to move at a remarkable speed to cover so much ground, but it is evenly paced, never hurried. I found the film to be marvelous in its minutest details. Smike is, if anything, deemphasized – he is an important character, since he is a part of Ralph Nickleby’s undoing, but his sad love for Kate Nickleby is kept secret by Nicholas (he alone sees her miniature portrait hidden under his pillow) and he isn’t used, as the RSC production does, as an almost embarrassingly deformed, gut-wrenching figure.

The film’s political punch is abundantly clear: Dickens’s honest, pure, stupid, hapless, luckless, grasping and avaricious people are all products of an economic system that is, in George Orwell’s words, “a free-for-all in which the worst man wins.” Yet Dickens could never leave the world the way he found it – lies must be exposed, wrongs must be righted, and good must prevail.

Cavalcanti assembled an excellent production crew, including Michael Relph (Dead of Night) as art director and Gordon Dines (The Cruel Sea) at the camera. Among his actors, Madeline Bray is played by Jill Balcon, the daughter of the film’s producer, in her first film acting role. She was also Daniel Day-Lewis’s mother.

(1) George Orwell, Essays, (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1996), p. 181.

(2) John Simon, “A Gold-Plated Nickleby,” New York, October 19, 1981.