James Taylor is one of the most enduringly popular recording artists of the past fifty years. Although a product of the Sixties, few people would think of associating him with the drug culture of the time, and even fewer people remember him as a serious addict, or "junkie." Yet Taylor claims that he fought an addiction to heroin for twenty years.

As he told The Rolling Stone in 2015, "I had taken my first opiate in 1966. Joel 'Bishop' O'Brien, the drummer in the Flying Machine, was an addict. I spent a lot of time at his apartment, so it was just a matter of time before I tried heroin. I was pretty much born to shoot dope - it was the key to my lock, so I really was gone for the next 20 years."

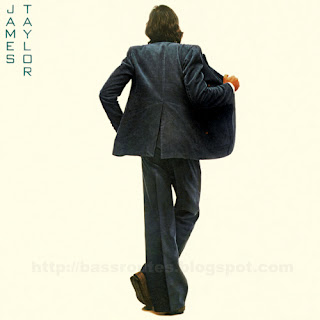

Taylor's 1976 album, In the Pocket is one of his richest, despite the fact that only one of the twelve songs it contains, "Shower the People," became a hit. Like many other of his recorded songs, the rest of the album has remained virtually unknown since its first release. Two songs from the album, which I'm somewhat ashamed to say I heard for the first time last year, have since acquired a special value for me. As a substance abuser myself (alcohol), I found myself identifying strongly with the words to Taylor's songs "Golden Moments" and "A Junkie's Lament," both of which paint vivid pictures of the highs and lows of addiction.

The song "Golden Moments" is disarmingly lovely. It's subject is bliss, but Taylor's lyrics to the song give one clues about the origin of the bliss:

Now if all my golden moments could be rolled into one,

They would shine just like the sun for a summer day.

And after it was over, we could have it back again,

With credit to the editor for striking out the rain - very clean.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna bring me down.

No one's gonna stop me now.

Now I gathered up my sorrows and I sold them all for gold,

And I gathered up the gold and I threw it all away.

It all went for a good time and a song - come on.

The laughter was like music, it did float my soul along - for a while.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna reach me here.

No one's gonna know I'm gone.

You may think I must be crazy, and I guess you must be right,

But I know the way I feel today is out of sight.

I do not trust my senses to remember your name.

Without corrective lenses, things are never quite the same - anyway.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna bring me down.

No one's gonna stop me now.

No one's gonna reach me here.

No one's gonna know I'm gone.

What else could Taylor be singing about, in such diaphanously dreamy music, but getting high? He wants to escape, to be where no one can find him, where no one can stop him (or criticize him). What better ticket to oblivion than heroin? Like all drugs with which people self-medicate, it is a disease but also its cure. Escape can only be temporary, but while we are in its thrall, nothing can touch us. The world recedes to a faint murmur, a distant commotion on the horizon.

Taylor was honest enough with himself to celebrate his highs, and to give us a vivid impression of what they were like - but he didn't fail to describe, in telling language, his lows. If addiction were nothing but a constant high, no one would want to be rid of it. But unless the highs are evened out with occasional lows, a drying out, being strung out, the addiction would lead to inevitable overdose and death.

The other song from Taylor's album In the Pocket that, ironically, is on Side B,(1) that relates to us the other side of addiction, is called "A Junkie's Lament." It is the perfect companion piece to "Golden Moments."

While never having tried heroin, I know where Taylor is coming from in the tellingly direct words to "A Junkie's Lament":

Rick's been kicking the gong, lickety-split, didn't take too long.

A junkie's sick, a monkey's strong, that's what's wrong.

Well, I guess he's been messing around downtown,

so sad to see the man losing ground.

Winding down behind closed doors

On all fours.

Mama, don't you call him my name.

He can't hear you any more.

Even if he seems the same

to you, that's a stranger

to your door.

Go on, ask him what's he come here for.

Oh my God, a monkey can move a man.

Send him to hell and home again.

An empty hand in the afternoon,

shooting for the moon.

It's halfway sick and it's halfway stoned.

He'd sure like to kick but he's too far gone.

They wind him down with the methadone.

He's all on his own.

But baby, don't you throw your love away.

I hate to seem unkind.

It's only that I understand the man

that the monkey can leave behind.

I used to think he was a friend of mine.

La la la la la la la la . . .

As Taylor explained to The Rolling Stone:

"I've got a lot of recovery songs. This one's ["A Junkie's Lament"] a warning not to think of a junkie as a complete functioning human being. Heroin should've killed me about five times, but it never did....People take drugs to be in control. They want to short-circuit any risk that they might take in life, any uncertainty, any anxiety. They just want to find the chemical route, to just push the button that gets the final result."

As I said, I didn't become acquainted with these two songs until the summer of 2015, during my last bad bender. Having been a habitual drinker since the death of my father in 1988, with occasional respites, all the way up until 2004, when I began to routinely experience serious withdrawals (without knowing exactly what they were at first), it was late that year that I discovered a dangerous solution to my withdrawals: the hair of the dog that bit me - i.e., continuous drinking. Eventually, this discovery contributed to my losing two jobs, which forced me to move in with my sister, abandoning an apartment full of furniture to fly from Des Moines, Iowa all the way to Anchorage, Alaska. Since then, however, I have interspersed extended stretches of sobriety with occasional benders. I never quite know what provokes them. They arrive out of the blue after sometimes months of abstention.

What I have learned is the same thing that Taylor evidently learned a much harder way: what every addict must face before he goes too far is the choice between life or death. He cannot go on using or he will end up dead. It's always the same choice: get clean and live or go on using and die. Choosing life has its obvious perks, but how enticing those beautiful dying notes from "Golden Moments" sometimes seem.

In the treatment of bi-polar disorder, physicians do us no favors by informing us that depression is nothing but a chemical imbalance that can be corrected with prescription drugs. What is happiness, then, but a similar treatable chemical imbalance? Having taken Prozac for awhile in 2006, during a long sober stretch, after about a month of low doses I suddenly felt as if someone had turned on all the lights. I was awake for the first time in more than a year. Unfortunately, the drug also made me more confrontational and argumentative, unsatisfied with my life. And within weeks I was drinking again. For the untreated, self-medicating user, withdrawals (depression) is the price he pays for getting high (happiness). What he must figure out - "all on his own" - is whether or not it is worth it.

(1) In actuality, the track listing for In the Pocket places "A Junkie's Lament" on Side A, Track 2 and "Golden Moments" on Side B, Track 6. Significantly, the album closes with Taylor's evocation of opiate bliss.

No comments:

Post a Comment