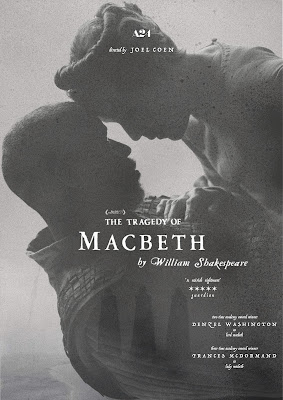

Out of the blue – or in this case the fog – here we have another film adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, this time directed by Joel Coen, one half of the Brothers Coen filmmaking team. Joel Coen’s wife, Frances McDormand, asked him to direct a stage version with her in the role of Lady Macbeth. He opted to direct a film of the play instead, and told Kenneth Turan, “I knew I’d be directing the next one by myself. If I was working with Ethan I wouldn’t have done ‘Macbeth,’ it would not be interesting to him.” As one who has been wondering for 30-odd years why the Coens make movies, this doesn’t supply me with an answer. The movies never did, either. But this one does.

Denzel Washington, who plays Macbeth in Coen’s film, is quite wrong to state that Shakespearean English is "a foreign language.” Shakespeare’s work seems distant to us because he wrote in poetic language. There are anachronisms, but only because some of the words are no longer in currency. But every word Shakespeare used is invested in the English language. We carry those words around with us every day of our lives. I have a religious friend who doesn’t like the King James Bible because it turns him off. He wants it to be clear, so he settled for one of the ponderous modern translations of the Bible. The KJV is written in the same language used in Shakespeare, and it has introduced, in the 400 years since its publication, exalted language to the homes and lives of English speakers.

Peter Brook said, “Each line in Shakespeare is an atom. The energy that can be released is infinite—if we can split it open.” Like every other play, Shakespeare’s live through their words, and the best medium for those words is the theater. But more than a hundred movies have been made from Shakespeare plays. The best Macbeth I’ve seen (until now) is Roman Polanski’s from 1971. It did the play’s bloodiness justice. It was scenically realistic, which didn’t clash with the language, since medieval Scotland is as exotic as the words.

The first thing Joel Coen did right in the making of his The Tragedy of Macbeth is dispensing with any pretense of realism. His film was shot exclusively on sound stages and the flat absence of any recognizable place throws his entire production – and we his audience – back on the words themselves. And for this service to the play, Joel Coen deserves praise. The settings for every scene are functional merely as settings. They serve no other purpose, so the audience quickly learns to ignore them.

In so many of his film roles, Denzel Washington was a fighter and a killer, so the very first of his murders – Duncan’s – , though brutal (Macbeth covers his mouth and stabs him in the throat) seems almost natural. But there is a world of difference when it is encased in enthralling language. Washington may have seemed so right for the role, but Coen makes it seem as if all of his prior violence – a career’s worth – was a rehearsal, practice, for the violence he does here.

Macbeth is a sympathetic, even heroic, character until the assassination of Duncan. Carrying the weight of the Witches’ – or the Witch’s, since “they” are played, startlingly, by one actor – foretelling, at first he actually balks at actively fulfilling it. It is Lady Macbeth who spurs him on. Macbeth knows this. “Bring forth men-children only” he tells her, “For thy undaunted mettle should compose Nothing but males.” And carrying out his murders gives Macbeth a kind of divine invincibility and impunity. He is no stranger to the slaughter of men, women, or children, except that before he committed the acts under orders. Now he must fulfil a prophecy, under divine orders and under the direction of his wife.

Coen commits to some novel interpretations of the text. For instance, when Macbeth asks “Is this a dagger I see before me?” it’s nothing but the handle of a door – the door behind which Duncan sleeps – shining in the moonlight. From this we learn that Macbeth isn’t so susceptible to the supernatural, especially as he is about to murder Duncan.

If greatness eludes this filmed Shakespeare, it's because of the absence of a great performance. Denzel and Frances McDormand are both excellent. I was amazed at his command and assurance in the role. One of his best speeches, trying to explain why he killed the apparent killers of Duncan, he delivers with a quite moving conviction:

Who can be wise, amazed, temp’rate, and furious,

Loyal, and neutral, in a moment? No man.

Th’ expedition of my violent love

Outrun the pauser, reason.

Who could refrain

That had a heart to love, and in that heart

Courage to make ’s love known?

On hearing these words, Frances McDormand swoons.

The most fascinating performance in the film is from Kathryn Hunter, who plays all three of the witches (she speaks their lines as if she were talking to herself), and a white-haired old man who hides Banquo’s son. Coen represents the three “weird sisters” as three crows, and at one point, Kathryn Hunter caws like a crow and moves uncannily like one before throwing on her long cloak. Though she stands alone on beside a puddle of water, she casts two reflections. Macbeth and Banquo address them in the plural.

But something happens as the climax of the tragedy approaches – a kind of lethargy overtakes the production, but not because we know how it will end. The dead leaves bursting into Dunsinane when the English army lays down the boughs from Birnam Wood are beautifully eloquent. They’re symbolic of all the children that Macbeth has killed, as well as the children Lady Macbeth never gave him. But the "Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow..." speech falls flat, and I suppose that the last sword fight was unavoidable. As swordfights go, it’s rather dull. Denzel is much better with daggers.

Harold Bloom, in his book Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human, stated that Akira Kurosawa’s film Throne of Blood was "the most successful film version of Macbeth". How this is possible in the total absence of the text is puzzling. What he meant, I think, is that it comes closest to evoking the atmosphere of the play. Joel Coen is familiar with Kurosawa’s film, which was shot in black & white on the fog bound slopes of Mt. Fuji. I thought Kurosawa’s film was a worthy experiment, but that it teeters from the daunting effort of replacing the missing blank verse with suitably vivid imagery.

Coen’s film is, I think, something of an ideal Shakespeare film. Everything is minimized so that the words can do their work.

No comments:

Post a Comment