I have always admired the sweet dignity in Robert Frost's short definition of "Devotion":

The heart can think of no devotion

Greater than being shore to ocean

Holding the curve of one position

Counting an endless repetition.

The film Amour (2012), however, explores the indignities that befall us when we find that our repetitions are not endless - when the countdown to death begins. But it also asks us if it is truly the end of love or only a transition. It seems to answer that age-old question of the poets: what becomes of the beloved?

Austrian filmmaker Michael Haneke has made a substantial reputation for

creating works that combine a preoccupation with often brutal subjects and a formal coolness. In The Piano Teacher, the surface quietude of a woman's life is torn apart by a sado-masochistic affair with a much younger man. In Caché, a successful television host becomes the object of blackmail by a figure from his less than innocent childhood. In The White Ribbon, the serenity of a typically jewel-like German village before the First World War is ruffled by a series of increasingly disturbing incidents.

Amour (2012) involves us in the lives of Georges and Anne, both retired music teachers, enjoying what have come to be known as their "declining years." They live in a lovely old Paris apartment, of which we are given a brief tour when the film opens by the police, who have responded to complaints of a foul odor emanating from inside. They break down the doors and find the body of a dead woman lying on a bed, her head surrounded with flower petals. There is no one else, alive or dead, in the apartment, which leads us into one of the film's unexplained mysteries.

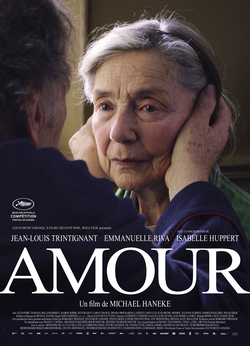

In the following scenes we are introduced to Georges and Anne, played by the venerable Jean-Louis Trintingnant and Emmanuelle Riva, who return from a concert one evening to find evidence of an attempted break-in to their apartment. Although the attempt is evidently unsuccessful, Anne is so disturbed by the event that it brings on a stroke, evidence of which appears the following morning when she goes "blank" at the breakfast table. Jumping forward in time, Georges discusses an unsuccessful operation on Anne with their daughter, played by Isabelle Huppert (who was formerly Haneke's Piano Teacher), and Anne is brought back to their apartment in a wheelchair.

These two people, proud of their accomplishments in life and of their place in the world, have nonetheless reached a tacit pact with each other, should their advancing years place either of them in a position of unavoidable and inescapable difficulty. Out of either shame or pride, Anne arrives at the decision to allow no one - not even her daughter - to see her deteriorating condition. Finally, when she is unable or, more likely, unwilling, to swallow some water that Georges tries to get her to drink, he reacts by slapping her. Can this possibly be looked upon as an access of tenderness? Even though he is ambulatory and is free to leave their apartment, he behaves as if he knows that her fate is his as well. He is as incapacitated as she. And because he is still marginally in control, he commits an act, in gently suffocating her with her pillow, that could be viewed (certainly from a legal perspective) harshly.

Haneke has been accused of being brutal by showing us the details of Anne's steady decline - how, for example, Georges helps her get off the toilet, pulling up her panties and, in a kind of broken pas de deux, moving her through the narrow bathroom door. Or when Anne pees the bed, and is overcome with the humiliation. It isn't Haneke's brutality but life's that he shows us. His film reminded me of the last scenes of Iris (2001), in which John Bayley (Jim Broadbent) endures the torments of the final stages of Iris Murdoch's (Judi Dench) alzheimer's.

I mentioned Haneke's formal coolness. His are the most meticulously composed films since Antonioni. His camera takes up a witness point that is only as engaged as Georges and Anne's apartment will allow. It is such a comfortable and lived-in space for the couple, who eventually, as the solitude of Anne's illness progresses, are the only people onscreen, that it becomes a kind of echo chamber. Anne looks through an album at photographs of herself, Georges and their daughter from half a century ago and remarks on their long, beautiful life - a life that is coming to a close.

We are shown Georges's dreams, some suffocating, others nostalgic, all of which are confined, like him, within his apartment. Finally, with Anne's body arranged in her bed among flower petals, Georges dreams she is there again, alive, and they depart together through the door that their daughter enters, seconds later, but after the apartment has been cleared. We are left to presume that Georges has died, too - although it is only Anne's body the police find. We see him carefully writing a long letter. Is it a suicide note? To whom is it addressed?

Haneke's camera (Darius Khondji was his DP) observes carefully but selectively, knowing when to be clinical and when to make the viewer guess at what is happening. The decor is uncluttered but apposite, but two things - a television and a computer - are conspicuously absent. In the salon, there are only a piano, books, and recorded music. The only music we hear in the film is played on a piano or on a music system.

Then there are the two actors. It would be very hard to find two who wear their age so beautifully. Unlike Hollywood actors, who undergo cosmetic surgeries to disguise themselves as younger people, these storied French actors are also human beings. I saw a recent photo of Jean-Paul Belmondo and Alain Delon last week. Both men are pushing 80 and they look it. Look at Warren Beatty and Jane Fonda. It's rather terrible that our superficial culture has forbidden them to grow old. I have recently seen Trintingnant in two films - Dino Risi's Il Sorpasso and a very minor French film from 1964, Les Pas Perdus, with Michèle Morgan. Trintingnant was the perfect foil to Vittorio Gassman in the former, and surpringly affecting as a gigolo with a heart in the latter. (Michèle Morgan, the siren of French poetic realism, died at the end of last year at the age of 96.) In Amour Trintingnant is the same quiet, intelligent presence. Emmanuelle Riva was one of the reasons that Hiroshima Mon Amour was - and remains - worth watching. Although the equation of the suffering of her character with the suffering of Hiroshima was insubstantially argued (in Marguerite Duras's script), Riva gave it all the heft and gravity it would've needed. It is she, not the Japanese gentleman (played by the late Eiji Okada), who insists on dredging up the past, which further invalidates Duras's labored point. Riva, still beautiful, is quite affecting in Amour. Her decline is all the more saddening for being so honestly presented.

In one of his characteristically brilliant but rather slanted essays, "Bourgeois Nightmares," the late Gilberto Perez wondered about Haneke's "happy ending":

"Earlier in the film a pigeon flies in through the window in the entrance hall, and Georges helps it fly out. After he kills Anne, it flies in again, but this time Georges gets up from his writing, shuts the window and captures the pigeon in a blanket. He writes that he let the pigeon go, but we never see him do it. He stays alone in the apartment. From his bed he hears the sound of water off-screen: Anne is there, washing the dishes in the kitchen. I’m almost finished, she says, put on your shoes if you want. She puts on her coat and reminds him to take his as she opens the door of the apartment and they go out for the evening. The shot is held after they leave. No doubt this is a dream, but it suggests something like their entering the afterlife together. Asked to comment on the pigeon, Haneke has observed that they often fly into Parisian apartments. But this one might represent the freedom from confinement that Georges refuses following his wife’s death, then accepts in his dream. Perhaps he flew out of the window, now open again, as the police noticed when they broke in."(1)

Haneke is certainly one of those directors who forces one to concentrate. But in support of his argument, Perez indulges in a somewhat creative solution to Georges' mysterious absence. But if his explanation is unacceptable, what other explanation is there? Where did Georges go, if not with Anne in his dream?

If we are left with questions at the film's conclusion, perhaps they are in accordance with Haneke's poetry. As another poet, Alun Lewis, put it another way:

Time upon the heart can break,

But love survives the venom of the snake.

("In Hospital: Poona")

(1) London Review of Books, 6 December 2012.

No comments:

Post a Comment