I have waited more than a month to make what will probably be my last post of this terrible year. Since its subject is Christmas, I am at least closing on an upbeat note.

I think Christmas is about memory - as much to do with what we did with Christmas in the past as what we do with it today. Like birthdays, however, it's hard to single out any specific year as especially memorable. I recall Christmases from 1974, 1995, and even a few from the years I have spent here in the Philippines. But the one that stands out for me as My Best Christmas was in 2005. Here's why.

I had been living in Des Moines, Iowa since 2001. A failed marriage took me there, and almost five years later an engagement that fizzled out resulted, eventually, in my having to get out of town. Actually, it's what happened to me after the collapse of my engagement that forced me to leave town. Because of the cumulative effects of heavy drinking, I lost two jobs and, realizing, in mid-December, that I was in the perilous position of not having enough time to find another job to pay the next month's rent, I had to find someone who would give me refuge. It was that or end up homeless in Des Moines - in January.

First I contacted some of my closest friends. Only one was willing to take me in. The rest were very involved in complicated domestic arrangements of their own. Then I contacted my brother in Denver. He surprised me by suggesting that I call my sister in Alaska, whom I hadn't seen since 1998. My brother gave me her number, and I called her.

After telling my sister about my predicament, she told me that she would only be too happy to take me in, that her door was always open for me. I couldn't speak over the long-distance line for several seconds as I wept for joy, and she kept calling out my name and saying "Hello?" fearing the line had been disconnected. After regaining my composure, I thanked her copiously and asked her when I could come.

I first thought of renting a van and driving the distance north through Minnesota and across half of Canada, which would have been a difficult drive in July. In December, at those latitides, the hazards were unimaginable. So my sister laid out the only other plan of action that would work - to gather up everything that I couldn't part with, pack it into boxes and ship it to her using "Media Mail" - the cheapest method available through the U.S. Postal Service.

She sent me enough money to ship about a dozen boxes, which I carried from my apartment in downtown Des Moines to the Post Office a few blocks away. Some of them weighed thirty or forty pounds, so the trudge to the Post Office every day was strenuous.

Once the last package was mailed, I turned in my key at the apartment manager's office, called for a taxi and caught a flight to Anchorage. I left behind in my apartment all the furniture I had bought for a married life that never transpired - a queen-sized bed, a big screen TV, book cases, and a desk. I owed nothing for the furniture, since I had already gone bankrupt in August.

It was nine years ago to this very day - the afternoon of 23 December. I flew first to Minneapolis, and then onward to Anchorage. All I could see in the starlight from my window seat was a world of white below - whether clouds or fields of snow I couldn't tell.

On the approach to Anchorage, I looked down on Cook Inlet covered in ice. The Inlet was named for Captain James Cook, who "discovered" it whilst looking for the mythical Northwest Passage. Coming in for a landing, I saw snow, snow, snow . . . and at last the black tarmac. The plane touched down, I deplaned and collected my luggage. It wasn't until I walked out of the main terminal that I heard a voice yell, "There's my little brother!" I saw a woman approaching me and thought for a split second that it was my mother - who had died in 1998. It was my sister, who had become at that moment my whole family in one person.

The air was frigid. Everything was covered in snow. My sister took me to her burgundy Ford Explorer, that she had long since named "Victoria," and drove me across Anchorage to her house at the nub of a cul-de-sac, where she lived with her two dogs and several teddy-bear hamsters. It was a relatively new house with a garage, a large downstairs living room, adjoined by a large kitchen, a front room by a big front window (where an untrimmed Christmas tree was standing). The steep stairs led to three bedrooms and a loft. My fold-out bed occupied the loft (right above the garage), and I don't remember much else from that night except going to bed.

The following day - Christmas Eve - was clear, crystalline. My sister decided that I should buy a few gifts for her, so she took me to Dimond - not Diamond - Mall and handed me a hundred dollars. Everything was on sale for the few crazy people who had waited so long to shop. I bought my sister a big (rather vulgar) crystal perfume dispenser and a wine decanter in the form of a chef.

Upon retruning home (such a beautiful word), we ate too much and watched some television. And when the sun went down at about four o'clock, my sister got out the boxes containing all of our family's old Christmas tree decorations, some of them decades old, and together my sister and I trimmed her fat artificial Christmas tree. As we removed the decorations from the boxes, I recognized many of them and we shared memories of Christmases past. Finished, the moment came to light the lights. Standing there beside my sister, gazing at the exquisite tree with blinking lights, with the frozen yard and icy street visible through the front window, I felt something I hadn't felt since I left my parents' home: I felt the speechless joy of being with my family.

During the night, more snow fell and we awoke on a gloomy Christmas morning (with sunrise at about nine). I put on a CD of music by Vince Guaraldi composed mostly for the 1965 TV Special "A Charlie Brown Christmas." After breakfast, I helped her load numerous wrapped gifts into the back of her Explorer, and she took me around to the homes of all her friends to give them their gifts. She invariablty introduced me as her "little brother" (I was 47 years old), and they all told me how she had told them so much about me. Driving away from one house, my sister hit a curb and flattened a tire. With the temperature at what felt like zero, her friends came out and helped change the tire.

Back home, we watched, of all things, Home Alone 4, a film I didn't know even existed. Watching it, I learned why. Dinner consisted of a small turkey, cooked in a rotisserie oven, a ham, and the usual side dishes of stuffing, cranberry sauce, and mashed potatoes. I don't recall exactly what we had for dessert. It was probably pastries bought from a bakery. When we were done, we watched Turner Classic Movies, which my sister watched religiously, long into the dark night.

My sister knew, as the saying goes, how to keep Christmas well. I got about ten gifts from her that year, including a remote-control model helicopter. She had read somewhere that every man wants a toy for Christmas. I didn't want a toy for Christmas, but who was I to argue? After such a frightful year, in which my dream of being married again blew up in my face, and after a bankruptcy and losing two jobs to alcohol abuse, it was the happy ending I could only have dreamed of having. And I owed everything to my sister, who (once again) saved me from my life.

Merry Christmas, Bibbit, wherever you are.

Friday, December 23, 2016

Tuesday, December 6, 2016

A Hyper Life

Elizabeth Jane Moreno Gueci Eichner Roberge Michaels, née Harper, was born 22 July 1951 in Stuttgart, West Germany, the second daughter to George Wesley and Alice Jane Harper. He was a career soldier and she was a homemaker and nurse's aid.

Elizabeth, who went by Liza in her later years, graduated Cardinal Newman High School in Columbia, South Carolina, Class if '71. She briefly attended the University of South Carolina. The first of five husbands, Ricardo Moreno, son of political science professor Nestor Moreno married her in 1971. Her only daughter, Amanda Cristina, was born in 1972.

Her other husbands were Joseph Gueci of New Jersey, Edward Eichner of Lincoln Nebraska, Robert Roberge of Denver, and Shane Michaels of Anchorage, Alaska. The third, fourth and fifth survive her. She explained to me that when she falls in love, she feels like she's inside a beautiful, protective bubble, but that, soon after she marries a man, she finds that the bubble has somehow burst. It is entirely outside her control.

When our mother had a stroke during pregnancy at the age of 40, I was brought home alone by our father. Since career soldiers made very low salaries at the time, he could not afford a nurse. Elizabeth, aged 7, became my surrogate mother until, after months of physical therapy in which she had to learn how to speak, walk, and write all over again, our mother returned from the hospital. Having known her prior to the devastating stroke as a loving and gentle woman, my sister was introduced to a woman who was emotionally unbalanced. The slightest stress would send her into hysterics. Elizabeth never recovered from the shock, and thereafter her relationship with our mother was close but strained. Upon our mother's death in 1998, Elizabeth moved to Anchorage, Alaska, where she spent the remaining eighteen years of her life. She loved Alaska, the snow and the cold. I invited her to come and live with me in the Philippines, but for several reasons, one of which was her intense dislike of hot weather, she wouldn't come.

Elizabeth's profession from the early 1990s was medical transcriptionist, at which she was perfectly proficient. But in 2006, technological advances and outsourcing slowly eliminated it as a reliable source of income. In Alaska she took up designing and creating hand-crafted crystal jewelery, offering her work for sale at various bazaars in and around Anchorage until she became physically unable to set up her tent and the tables inside. A home she mortgaged through Wells Fargo became another victim of foreclosure in late 2007 during the collapse of the American real estate market. She lived in apartments from then until her death on 27 October at the age of 65. She is survived by her two brothers, her daughter, two grandchildren and three surviving ex-husbands. The exact cause of her death has yet to be divulged to me. A medical checkup a month prior to her death lists among her complaints a longstanding depression and suicidal thoughts. On three occasions since I left the States I had to call the Anchorage Police Department to check in on her. Lately I have even enlisted the help of some Facebook friends who are considerably closer to her than I am. Their help was above and beyond.

On the two occasions when my life hit a wall, in 1995 and in 2005, my sister took me in without question or criticism. Even if I set about paying back all the money I owed her in monthly increments, I would never have paid it all back even if she'd lived to be 100. What I owe her emotionally and psychologically is inestimable.

She was a force of nature - a ball of nervous energy that she expressed in utterly unapologetic impulsive behavior. I could never keep up with her. I would accompany her somewhere, like WalMart, and upon leaving the car the race was on. By the time sje was in the middle of the store and turned to say something to me, I was usually a hundred yards behind her.

Her health was failing last Spring and she spent a month in the hospital. Aside from the physical trauma, I don't think she quite recovered from the shock of her body betraying her. The wrong combination of a variety of new medications may have contributed to her death. I just don't know for sure and may never know.

When you lose someone who has known you all your life, it is as if a wonderful road into the past down which you were once able to travel freely has become suddenly impassable. Losing my big sister leaves a giant hole in my life that can never be filled.

Elizabeth Jane Harper - who was and will always be known as Bibbit to my brother and I - July 22, 1951 - October 27, 2016.

In the words of Johnny Mercer,

I should be over it now I know

It doesn't matter much

How old I grow

I hate to see October go.

Elizabeth, who went by Liza in her later years, graduated Cardinal Newman High School in Columbia, South Carolina, Class if '71. She briefly attended the University of South Carolina. The first of five husbands, Ricardo Moreno, son of political science professor Nestor Moreno married her in 1971. Her only daughter, Amanda Cristina, was born in 1972.

Her other husbands were Joseph Gueci of New Jersey, Edward Eichner of Lincoln Nebraska, Robert Roberge of Denver, and Shane Michaels of Anchorage, Alaska. The third, fourth and fifth survive her. She explained to me that when she falls in love, she feels like she's inside a beautiful, protective bubble, but that, soon after she marries a man, she finds that the bubble has somehow burst. It is entirely outside her control.

When our mother had a stroke during pregnancy at the age of 40, I was brought home alone by our father. Since career soldiers made very low salaries at the time, he could not afford a nurse. Elizabeth, aged 7, became my surrogate mother until, after months of physical therapy in which she had to learn how to speak, walk, and write all over again, our mother returned from the hospital. Having known her prior to the devastating stroke as a loving and gentle woman, my sister was introduced to a woman who was emotionally unbalanced. The slightest stress would send her into hysterics. Elizabeth never recovered from the shock, and thereafter her relationship with our mother was close but strained. Upon our mother's death in 1998, Elizabeth moved to Anchorage, Alaska, where she spent the remaining eighteen years of her life. She loved Alaska, the snow and the cold. I invited her to come and live with me in the Philippines, but for several reasons, one of which was her intense dislike of hot weather, she wouldn't come.

Elizabeth's profession from the early 1990s was medical transcriptionist, at which she was perfectly proficient. But in 2006, technological advances and outsourcing slowly eliminated it as a reliable source of income. In Alaska she took up designing and creating hand-crafted crystal jewelery, offering her work for sale at various bazaars in and around Anchorage until she became physically unable to set up her tent and the tables inside. A home she mortgaged through Wells Fargo became another victim of foreclosure in late 2007 during the collapse of the American real estate market. She lived in apartments from then until her death on 27 October at the age of 65. She is survived by her two brothers, her daughter, two grandchildren and three surviving ex-husbands. The exact cause of her death has yet to be divulged to me. A medical checkup a month prior to her death lists among her complaints a longstanding depression and suicidal thoughts. On three occasions since I left the States I had to call the Anchorage Police Department to check in on her. Lately I have even enlisted the help of some Facebook friends who are considerably closer to her than I am. Their help was above and beyond.

On the two occasions when my life hit a wall, in 1995 and in 2005, my sister took me in without question or criticism. Even if I set about paying back all the money I owed her in monthly increments, I would never have paid it all back even if she'd lived to be 100. What I owe her emotionally and psychologically is inestimable.

She was a force of nature - a ball of nervous energy that she expressed in utterly unapologetic impulsive behavior. I could never keep up with her. I would accompany her somewhere, like WalMart, and upon leaving the car the race was on. By the time sje was in the middle of the store and turned to say something to me, I was usually a hundred yards behind her.

Her health was failing last Spring and she spent a month in the hospital. Aside from the physical trauma, I don't think she quite recovered from the shock of her body betraying her. The wrong combination of a variety of new medications may have contributed to her death. I just don't know for sure and may never know.

When you lose someone who has known you all your life, it is as if a wonderful road into the past down which you were once able to travel freely has become suddenly impassable. Losing my big sister leaves a giant hole in my life that can never be filled.

Elizabeth Jane Harper - who was and will always be known as Bibbit to my brother and I - July 22, 1951 - October 27, 2016.

In the words of Johnny Mercer,

I should be over it now I know

It doesn't matter much

How old I grow

I hate to see October go.

Friday, November 11, 2016

The Deserted City

Imagine that you are living in a modern, bustling city with a population in the hundreds of thousands and you wake up one morning to discover that everyone in the city has mysteriously vanished, as if, while you were sound asleep, every single resident of the city had been vacated or evacuated for reasons that are unknown to you.

Just before he died of tuberculosis in January 1950, George Orwell confided in a letter to a friend that he was having recurring dreams of finding himself alone in a deserted city. Fearless to the end, and without knowing that his own death was imminent, Orwell self-diagnosed the dream as a fear of death.

Something like this nightmare scenario was enacted in a movie I remember seeing when I was ten or eleven years old called The World, the Flesh and the Devil, which was made in 1959. It was a quite direct presentation of the consequences of a worldwide nuclear war. A mine inspector named Ralph Burton (played by Harry Belafonte) is down a mine in Pennsylvania when there is a cave-in and he is pinned, unconscious, under a beam. When he revives, he hears workers digging him out. But after a few days the sounds suddenly stop. After Ralph manages to dig himself out, he discovers that everything is inexplicably deserted. He finds newspapers with headlines describing a worldwide nuclear catastrophe - not from atomic explosions but a poison cloud that circled the earth for several days, wiping out all forms of life. (Quite implausibly, there are no bodies to be found anywhere.)

Ralph drives to New York City looking for some sign of life, but finds the city deserted. It was this point in the movie that I remember most vividly: images of the empty streets of Manhattan and Ralph despondently searching for someone, anyone. He manages to get power restored to a high rise building, taking up residence in the penthouse. He brings a department store mannequin to his flat, names him Snodgrass (he pronounces it "Snuffgrass") and has conversations with him. Just when he seems to be cracking up from his solitude, he throws Snodgrass off his penthouse balcony. When the mannequin hits the pavement below, Ralph hears a woman's scream. A toothsome blonde (thank you, Hollywood) named Sarah, played by the eternally toothsome Inger Stevens, had been following him and was afraid that Ralph had jumped to his death.

The injection of an interracial love story might have been ballsy in 1959, but, for me, the movie veered off course thenceforth. Things get even sillier when another man (white Mel Ferrer) shows up before Ralph and Sarah can surmount the racial divide and the film ends with the promise of a menage a trois, the three human survivors walking hand in hand away from the camera and the film closing with the title The Beginning. But the only reason that The World, the Flesh and the Devil has stayed for so long in my memory is due the startling pictures of a city forever stilled by a man-made catastrophe. A soundless, strangely alluring abandoned stage - civilization's end.

I don't dream of deserted cities, but it has become a compelling image for me since the death of my sister two weeks ago. The world feels somehow like it has collapsed. It has grown colder, like the time of year. Familiar places are less recognizable. Where the presence of my sister was, where the promise of Family once stood, there is now vacant space. I have lost all interest in Alaska, where she was living. Its natural wonders, its enormous open spaces, under the drifting snow of oncoming winter, a winter now endless, have lost all their allure. And since she has been cremated, she will have no resting place there to be visited some day, some flowers to leave on the ground - sweets to the sweet.

Even the people among whom I live (a girlfriend, her daughter) seem less familiar than they did. Their sympathy and support have helped me over the shock of losing my sister, but there is a point at which their continuing to live, going about their undisrupted lives, becomes intrusive - an affront to the prevailing sadness. Instead of morning greetings and coffee and breakfast, I feel that there should be lowered voices and muffled footsteps. the cat should be prevented from mewing with a saucer of milk, the television on but the sound turned low.

Saturday, November 5, 2016

Turn Off the Lights

On October 10 I published "A Sad Year" on this blog, descanting on all the terrible events that this year had by then inflicted on my family and I. Incredibly, impossibly, eighteen days later one more crushing blow fell.

I watched Jimmy Fallon the other day and Patton Oswalt spoke about how, since the death of his wife last April, grief now catches him unexpectedly at the oddest moments. He was updating an app and he thought about how his wife's apps will never be updated and he found himself weeping.

The British have a saying that accounts for the sudden chill one sometimes feels when a certain thought or memory catches one unawares: A ghost just walked over my grave. It's the same feeling Basho felt when, barefoot in his home, he steps on his dead wife's comb. An existential murmur, an intimation of mortality.

Thomas Hardy's late poems inspired by the death of his wife seem fixated on someone who is no longer there:

A NIGHT IN NOVEMBER

I marked when the weather changed,

And the panes began to quake,

And the winds rose up and ranged,

That night, lying half-awake.

Dead leaves blew into my room,

And alighted upon my bed,

And a tree declared to the gloom

Its sorrow that they were shed.

One leaf of them touched my hand,

And I thought that it was you

There stood as you used to stand,

And saying at last you knew!

(?) 1913

This is all that I know for now. It was on the morning of Thursday, October 27 in Anchorage, Alaska that her friend found my sister dead. It was early in the morning on Friday, October 28 on my island in the Philippines. When I arrived here from the States I created a chart showing the time in every time zone relative to the Philippines. When it was 8pm Eastern Savings Time on Thursday in New York City, it was 8am on Friday on my island. And Anchorage is four hours behind New York, so it was 4pm. Her friend did the only thing she could think of doing - she called 9-1-1. I was already awake and online, but her friend didn't send me an email and a message on Facebook until 1pm on Friday (5am my time).

I had finished my daily exercise at 10:30am on Saturday morning and my step-daughter told me it was my turn to go online. As soon as the wifi on my tablet activated, I got the email notification. I was surprised that my sister's friend, who hadn't communicated with me since March, when my sister was in hospital, was reaching out to me. But I thought nothing more of it until I went upstairs to my bedroom and laid down. Just as I was about to touch the icon to open the email, I froze. I knew that there had to be something wrong - otherwise she wouldn't have sent me an email. As soon as I opened it and read the first few lines, I couldn't read any more: "hey Danny, with great regret and sadness comes some very bad news...your sister, Liza has passed away....." The time stamp was Saturday at 5:12am, which means she sent it at 1:12pm Friday. So she had probably got my sister's landlord to let her in (he had to do the same thing in March) and discovered her dead on Thursday morning.

The EMTs responded, along with the police to take down the details for a death certificate. I don't yet know what they entered as the cause of death. I was awake in the wee hours because the speed of the internet is fastest when everyone is asleep. But I didn't know until later that morning what had happened 5,500 miles away in Anchorage. That's the distance "as the crow flies" between where I live and where she lived.

Here is what I have surmised this past week, not knowing my sister's official cause of death. Despite her friend's suggestion that her death was probably accidental - that she somehow made the wrong combination of her meds, and until I'm informed of a different conclusion, I think that she probably took an overdose.

I know all about the general reluctance of people to draw such a conclusion - even in their own heart of hearts. But I think that arriving at such a conclusion - and speaking openly about it - is one of the ways we can show our respect for the dead. Besides, it's too late for bullshit. Drawing a veil over a person's last moments, their final minutes and seconds of consciousness - especially when they have come, in their desperation, to such a conclusion - is a terrible disservice. Instead of dying by accident, their death is purposeful and carries with it the ultimate rebuke to the living.

She threatened to do it once before. In 2010, living on the same Philippine island, I received an email from my sister in which she told me that she was going to take an overdose of sleeping pills, that she loved me, and said goodbye. I didn't have wifi at home then. I had to use an internet cafe every so many days. I didn't read her email until three days after she sent it. By phone and at ridiculous expense I contacted my brother first (who assured me that my sister wasn't serious) and then Anchorage P.D. I was cut off twice while I related to the dispatcher my sister's name and address. By the time I called back a second time, the dispatcher told me that a patrol had already stopped by my sister's apartment and that she was well. I explained to my brother that even if she wasn't serious about taking her own life, even if her gesture was nothing but a "cry for help," someone needed to answer, if only to let her know that someone cared.

Living in Anchorage is expensive. A one-bedroom apartment costs more than $800 a month. My sister's profession - medical transcription - is being outsourced and outmoded by automation. At 65, her health was failing but she was finally eligible for Medicare. Her income had been reduced to the Social Security checks she got every month. Since the likelihood of getting myself to Alaska was a dim prospect, I offered to take her into my home here in the Philippines. Her monthly Social Security check would translate into a king's ransom, I told her. But she told me it was impossible. She would have to sell everything she owned and buy a plane ticket, which was simply too much for her to pull off in her condition.

By early October, I hadn't heard from her for more than a month. Since calling her was beyond my means (my only cellphone no longer has a charger), I enlisted my Facebook friends for help. After finally reaching her voicemail, one of my friends left her a message to contact me. The next day she responded on Facebook that she had had another health scare but that she was OK. A few days later, she posted the following on my Facebook timeline:

"Oct 21 9:14pm Listening to Last Train Home by Pat Metheny, looking outside my second storey window watching the first snow of the season, and an indescribable peace fills me. I remember watching the first snow the year Danny joined me in my house in Alaska, and all the times we'd sit in the great room and watch it snow, watch it snow. Such an incredible feeling knowing my favorite person in the world was with me and I wasn't alone. I love you Danny and wish you were here with me right now. Hot chocolate, a real fire going, music, and us. Bibbit."

A week after she posted this on Facebook, my sister was dead. When someone so close to you dies, it forces you to examine everything you said to them in their last days. Last June she emailed me in a fatalistic mood. To spite her, I sent her Philip Larkin's poem "Aubade":

Aubade

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.

The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse

- The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused – nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never;

But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear – no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.

And so it stays just on the edge of vision,

A small unfocused blur, a standing chill

That slows each impulse down to indecision.

Most things may never happen: this one will,

And realisation of it rages out

In furnace-fear when we are caught without

People or drink. Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Let’s no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can’t escape,

Yet can’t escape. One side will have to go.

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

I wanted to confront her with what Philip Larkin described so succinctly: death as a blunt fact. Her response, however, was typical: "That was unusual. Where do you find these things, Danny?

Almost four years ago on this blog I wrote a tribute to my sister [see Dear Sister] and I included the speech from the end of Tennessee Williams' play The Glass Menagerie. But I omitted the last telling line from the speech in which Tom says goodbye to his sister Laura. Here, now, is the complete speech. (I included Williams' stage directions.)

TOM: I didn't go to the moon, I went much further - for time is the longest distance between places. Not long after that I was fired for writing a poem on the lid of a shoebox. I left Saint Louis. I descended the step of this fire-escape for a last time and followed, from then on, in my father's footsteps, attempting to find in motion what was lost in space - I travelled around a great deal. The cities swept about me like dead leaves, leaves that were brightly coloured but torn away from the branches.

I would have stopped, but I was pursued by something.

It always came upon me unawares, taking me altogether by surprise. Perhaps it was a familiar bit of music. Perhaps it was only a piece of transparent glass. Perhaps I am walking along a street at night, in some strange city, before I have found companions. I pass the lighted window of a shop where perfume is sold. The window is filled with pieces of coloured glass, tiny transparent bottles in delicate colours, like bits of a shattered rainbow.

Then all at once my sister touches my shoulder. I turn around and look into her eyes ...

Oh, Laura, Laura, I tried to leave you behind me, but I am more faithful than I intended to be!

I reach for a cigarette, I cross the street, I run into the movies or a bar, I buy a drink, I speak to the nearest stranger - anything that can blow your candles out!

[ LAURA bends over the candles. ]

- for nowadays the world is lit by lightning! Blow out your candles, Laura - and so good-bye.

[ She blows the candles out. ]

Goodbye, dear sister.

Sunday, October 30, 2016

Vampyr

[In the spirit of Halloween, here's my take on a genuinely spooky film.]

When the Danish filmmaker Carl-Theodore Dreyer finished The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), which was critically acclaimed but a commercial failure, he decided to make what could only be described as a horror film, which he called Vampyr.(1) In 1931, Ufa, the film's distributor, held up its release until after the appearance of both Dracula and Frankenstein, hoping to capitalize on the craze for such films. That Dreyer's film is more subtle and imaginative with its horror effects than either Tod Browning's or James Whale's Hollywood productions contributed to its failure in Europe. While Bela Lugosi's vampire became an iconic figure, Dreyer's Vampyr fell into a long and undeserved obscurity. As late as 1949, Paul Rotha's invaluable monograph, The Film Till Now called it "A film, much applauded by the intelligentsia, its obscure mysticism, its diffused and meretricious photography, its vague hints of the supernatural, have let the film become very much of a museum piece."(2) There is nothing in the least mystical about Dreyer's film, the photography is often "diffused" (with the use of a gauze filter), but can hardly be called "meretricious" since the film was a commercial failure, and Dreyer's "hints of the supernatural" are anything but vague.

When the Danish filmmaker Carl-Theodore Dreyer finished The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), which was critically acclaimed but a commercial failure, he decided to make what could only be described as a horror film, which he called Vampyr.(1) In 1931, Ufa, the film's distributor, held up its release until after the appearance of both Dracula and Frankenstein, hoping to capitalize on the craze for such films. That Dreyer's film is more subtle and imaginative with its horror effects than either Tod Browning's or James Whale's Hollywood productions contributed to its failure in Europe. While Bela Lugosi's vampire became an iconic figure, Dreyer's Vampyr fell into a long and undeserved obscurity. As late as 1949, Paul Rotha's invaluable monograph, The Film Till Now called it "A film, much applauded by the intelligentsia, its obscure mysticism, its diffused and meretricious photography, its vague hints of the supernatural, have let the film become very much of a museum piece."(2) There is nothing in the least mystical about Dreyer's film, the photography is often "diffused" (with the use of a gauze filter), but can hardly be called "meretricious" since the film was a commercial failure, and Dreyer's "hints of the supernatural" are anything but vague.

I must admit that I am not a fan of horror movies. Even when I manage to find one that is effectively creepy, I find myself asking to what end does its creepiness lead?. I saw The Exorcist when I was 15 or 16 and it scared the hell out of me, but only because I hadn't yet made up my mind about the devil. My mother had brought my brother and I up on a diet of "Bucket of Blood Triple Features" at drive-in theaters, and I'm not ashamed to admit that I was afraid of the dark until I was 16. The movies were cheesy, schlocky, usually foreign-made, and laced with plenty of nudity. How my mother got my brother and I through the gate with all those R ratings is a mystery. Admission was "by the carload," so I guess the guy or girl at the gate never bothered to look at the occupants of the car.

Perhaps because they were never taken seriously by producers, few, if any, of the films classified as belonging to the "horror" genre were worthy of serious attention. However, when Vampyr was released it was still possible to take the genre seriously. After all, it was Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1921) that established it at a fairly high level of artistry. Even Dracula and Frankenstein, though incredibly sensationalizied, still have a degree of fascination about them, due to the performances of Lugosi and Boris Karloff.

Taking two stories from the gothic horror writer J. Sheridan LeFanu's collection In a Glass Darkly as his starting point, Dreyer, who was worried of becoming known as the "saint" director due to the overwhelming impact of The Passion of Joan of Arc, acquired the backing of Baron Nicolas de Gunzberg and avoided the expense of shooting in a studio by renting an abandoned chateau in the French town of Courtempierre. The chateau, in disrepair and infested with rats, provided him with just the right atmosphere of decrepitude and death for Vampyr. The Baron de Ginzberg, employing the screen name Julian West because his aristocratic family disapproved of his appearing in a film, played the role of the protagonist Allan Gray who arrives at "a secluded inn near the river in the village of Courtempierre."

Dreyer wastes no time establishing an atmosphere of weirdness: A man in a broad-brimmed hat rings the bell for the ferry. He carries an enormous and menacing scythe like the figure of Death. Once settled in his room at the inn, Gray hears a strange voice through a door leading to the stairwell and, looking up the stairs, is startled to see a man with no eyes emerge from a room. He returns to his room and locks the door but, lying in bed, the key is turned by an invisible hand and an old gentleman enters the room and paces pensively. When he notices Gray lying in bed, he goes to the window and opens the blind. Looking directly at Gray, he exclaims, "She mustn't die! You understand?" He then takes a small sealed parcel out of his pocket and writes on it, "To be opened upon my death." The gentleman leaves the same way he came.

These first scenes are shot virtually without dialogue, except for what I've quoted and three words spoken by a girl who runs the inn. In the early years of sound film, some producers resorted to making different versions of a film: one with German dialogue, one with French, English, etc. To avoid using the heavy and quite immobile sound cameras, Dreyer shot his film silent, adding the spoken dialogue, music, and sound effects in post-production. Dreyer's cinematographer for Vampyr was the great Rudolph Mate, who managed to move his camera fluidly around the film's cramped interiors, following the actors from room to room.

The rest of Dreyer's film involves Gray learning of a girl who lives in the chateau (whose father came to him at the inn) and is stricken by a strange illness. When he discovers she is the victim of a vampire, and that the vampire is being assisted by the village doctor, Gray helps to save the girl and destroy the vampire and the doctor.

Dreyer's cast is made up of mostly non-professional actors. I suppose it would've been too much to ask Baron de Gunzburg, having financed Dreyer's film, why he had to play the hero, Allan Gray. Tall, with unusually large eyes, he isn't required to give us much more in his facial expressions than the look of someone who has just sat on a tack. Otherwise he is utterly bovine.

At the film's end it is difficult to decide exactly what one has experienced. Dreyer indulges in atmospheric effects to create the cumulative effect of an hallucination. Although Gray himself has a vision in the film - the famous sequence in which he watches as his own body is buried alive, including shots through a window in the coffin lid - the entire film has the quality of a vision. Again and again I come back to the truly astonishing effect of a film: mobilizing forces, money and lives to capture images that end up as nothing more than shadows projected on a wall. The shadows captured by Dreyer in Vampyr are indelible, lingering in the memory many years after one has first seen them.

Ufa gambled on Vampyr capitalizing on the vogue for horror films created in Europe by Dracula and Frankenstein by delaying its release until after audiences had seen the two Hollywood films. Their gamble backfired when audiences, expecting a simple horror tale reinforced by expensive sets and elaborate makeup, became bewildered by Dreyer's non-linear style. Critics even condemned it as a ripoff of the vampire craze inspired by Dracula.

For Dreyer, who was his own producer for Vampyr, the failure of the film was so devastating that he suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be treated in a Paris clinic for three months. The name of the clinic - Clinique Jeanne d'Arc - must have seemed ironic to the beleaguered filmmaker.(3)

(1) Aka, Vampyr, or The Strange Case of Allan Gray.

(2) Richard Griffith, The Film Till Now.

(3) Information provided in Torben Skjodt Jensen's 1995 documentary, Carl Th. Dreyer - My Metier.

When the Danish filmmaker Carl-Theodore Dreyer finished The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), which was critically acclaimed but a commercial failure, he decided to make what could only be described as a horror film, which he called Vampyr.(1) In 1931, Ufa, the film's distributor, held up its release until after the appearance of both Dracula and Frankenstein, hoping to capitalize on the craze for such films. That Dreyer's film is more subtle and imaginative with its horror effects than either Tod Browning's or James Whale's Hollywood productions contributed to its failure in Europe. While Bela Lugosi's vampire became an iconic figure, Dreyer's Vampyr fell into a long and undeserved obscurity. As late as 1949, Paul Rotha's invaluable monograph, The Film Till Now called it "A film, much applauded by the intelligentsia, its obscure mysticism, its diffused and meretricious photography, its vague hints of the supernatural, have let the film become very much of a museum piece."(2) There is nothing in the least mystical about Dreyer's film, the photography is often "diffused" (with the use of a gauze filter), but can hardly be called "meretricious" since the film was a commercial failure, and Dreyer's "hints of the supernatural" are anything but vague.

When the Danish filmmaker Carl-Theodore Dreyer finished The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), which was critically acclaimed but a commercial failure, he decided to make what could only be described as a horror film, which he called Vampyr.(1) In 1931, Ufa, the film's distributor, held up its release until after the appearance of both Dracula and Frankenstein, hoping to capitalize on the craze for such films. That Dreyer's film is more subtle and imaginative with its horror effects than either Tod Browning's or James Whale's Hollywood productions contributed to its failure in Europe. While Bela Lugosi's vampire became an iconic figure, Dreyer's Vampyr fell into a long and undeserved obscurity. As late as 1949, Paul Rotha's invaluable monograph, The Film Till Now called it "A film, much applauded by the intelligentsia, its obscure mysticism, its diffused and meretricious photography, its vague hints of the supernatural, have let the film become very much of a museum piece."(2) There is nothing in the least mystical about Dreyer's film, the photography is often "diffused" (with the use of a gauze filter), but can hardly be called "meretricious" since the film was a commercial failure, and Dreyer's "hints of the supernatural" are anything but vague. I must admit that I am not a fan of horror movies. Even when I manage to find one that is effectively creepy, I find myself asking to what end does its creepiness lead?. I saw The Exorcist when I was 15 or 16 and it scared the hell out of me, but only because I hadn't yet made up my mind about the devil. My mother had brought my brother and I up on a diet of "Bucket of Blood Triple Features" at drive-in theaters, and I'm not ashamed to admit that I was afraid of the dark until I was 16. The movies were cheesy, schlocky, usually foreign-made, and laced with plenty of nudity. How my mother got my brother and I through the gate with all those R ratings is a mystery. Admission was "by the carload," so I guess the guy or girl at the gate never bothered to look at the occupants of the car.

Perhaps because they were never taken seriously by producers, few, if any, of the films classified as belonging to the "horror" genre were worthy of serious attention. However, when Vampyr was released it was still possible to take the genre seriously. After all, it was Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) and F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1921) that established it at a fairly high level of artistry. Even Dracula and Frankenstein, though incredibly sensationalizied, still have a degree of fascination about them, due to the performances of Lugosi and Boris Karloff.

Taking two stories from the gothic horror writer J. Sheridan LeFanu's collection In a Glass Darkly as his starting point, Dreyer, who was worried of becoming known as the "saint" director due to the overwhelming impact of The Passion of Joan of Arc, acquired the backing of Baron Nicolas de Gunzberg and avoided the expense of shooting in a studio by renting an abandoned chateau in the French town of Courtempierre. The chateau, in disrepair and infested with rats, provided him with just the right atmosphere of decrepitude and death for Vampyr. The Baron de Ginzberg, employing the screen name Julian West because his aristocratic family disapproved of his appearing in a film, played the role of the protagonist Allan Gray who arrives at "a secluded inn near the river in the village of Courtempierre."

Dreyer wastes no time establishing an atmosphere of weirdness: A man in a broad-brimmed hat rings the bell for the ferry. He carries an enormous and menacing scythe like the figure of Death. Once settled in his room at the inn, Gray hears a strange voice through a door leading to the stairwell and, looking up the stairs, is startled to see a man with no eyes emerge from a room. He returns to his room and locks the door but, lying in bed, the key is turned by an invisible hand and an old gentleman enters the room and paces pensively. When he notices Gray lying in bed, he goes to the window and opens the blind. Looking directly at Gray, he exclaims, "She mustn't die! You understand?" He then takes a small sealed parcel out of his pocket and writes on it, "To be opened upon my death." The gentleman leaves the same way he came.

These first scenes are shot virtually without dialogue, except for what I've quoted and three words spoken by a girl who runs the inn. In the early years of sound film, some producers resorted to making different versions of a film: one with German dialogue, one with French, English, etc. To avoid using the heavy and quite immobile sound cameras, Dreyer shot his film silent, adding the spoken dialogue, music, and sound effects in post-production. Dreyer's cinematographer for Vampyr was the great Rudolph Mate, who managed to move his camera fluidly around the film's cramped interiors, following the actors from room to room.

The rest of Dreyer's film involves Gray learning of a girl who lives in the chateau (whose father came to him at the inn) and is stricken by a strange illness. When he discovers she is the victim of a vampire, and that the vampire is being assisted by the village doctor, Gray helps to save the girl and destroy the vampire and the doctor.

Dreyer's cast is made up of mostly non-professional actors. I suppose it would've been too much to ask Baron de Gunzburg, having financed Dreyer's film, why he had to play the hero, Allan Gray. Tall, with unusually large eyes, he isn't required to give us much more in his facial expressions than the look of someone who has just sat on a tack. Otherwise he is utterly bovine.

At the film's end it is difficult to decide exactly what one has experienced. Dreyer indulges in atmospheric effects to create the cumulative effect of an hallucination. Although Gray himself has a vision in the film - the famous sequence in which he watches as his own body is buried alive, including shots through a window in the coffin lid - the entire film has the quality of a vision. Again and again I come back to the truly astonishing effect of a film: mobilizing forces, money and lives to capture images that end up as nothing more than shadows projected on a wall. The shadows captured by Dreyer in Vampyr are indelible, lingering in the memory many years after one has first seen them.

Ufa gambled on Vampyr capitalizing on the vogue for horror films created in Europe by Dracula and Frankenstein by delaying its release until after audiences had seen the two Hollywood films. Their gamble backfired when audiences, expecting a simple horror tale reinforced by expensive sets and elaborate makeup, became bewildered by Dreyer's non-linear style. Critics even condemned it as a ripoff of the vampire craze inspired by Dracula.

For Dreyer, who was his own producer for Vampyr, the failure of the film was so devastating that he suffered a nervous breakdown and had to be treated in a Paris clinic for three months. The name of the clinic - Clinique Jeanne d'Arc - must have seemed ironic to the beleaguered filmmaker.(3)

(1) Aka, Vampyr, or The Strange Case of Allan Gray.

(2) Richard Griffith, The Film Till Now.

(3) Information provided in Torben Skjodt Jensen's 1995 documentary, Carl Th. Dreyer - My Metier.

Tuesday, October 25, 2016

Freedom from Speech

By now, San Francisco 49er's quarterback Colin Kaepernick's decision not to stand during the pregame playing of the national anthem has been bandied about so much on both sides of the argument that the original reason for the protest has been overshadowed. As he explained after his first protest, he wanted to use his refusal to participate in the ceremony to bring attention to racial inequality and police brutality.

Many people saw his protest as a show of disrespect for the flag and for American servicemen and women and reacted in anger. When I expressed my own opinion of Kaepernick to my friends on Facebook, pointing out that good judgement was something that he neglected to learn in college all the while he was concentrating on throwing footballs to someone who could catch them, they made a point of defending the quarterback's right to free speech. This is what always happens when a protest, like the Black Lives Matter movement, degenerates into a free speech debate. Even when a Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsberg, chimed in on the subject, calling Kaepernick's actions "dumb," "ridiculous," "offensive," and "arrogant," social media erupted in harsh attacks on her. Probably amazed at the shitstorm her words elicited, Ginsberg has since walked them back, mollifying the same people who had cheered her the last time she shot her mouth off, dismissing Donald Trump a few weeks before. Her critics were merely citing the First Amendment, somehow forgetting that the Justice's job is to remind people of their Constitutional rights.

My remarks about Kaepernick's protest - and Justice Ginsberg's - were a response to the protest itself, the form in which Kaepernick chose to express his protest. I didn't say anything about depriving him of his right to make the protest. So why is everyone so vehemently (and so safely) citing the man's First Amendment right in response to everyone who disagrees with the manner - not the substance - of his protest? Why was Kaepernick's freedom to speak, by taking a knee, worthy of merit and mine (and Justice Gibsberg's) was not?

When I first learned of it, I thought about the reason - the real reason, not the avowed reason - for Kaepernick's distaste for having to stand up before every game. I thought about all the times I, too, had to stand up in movie theaters on military posts throughout my life, from when I was a boy into middle age before I left the Army at 42, in Albany, Georgia, Columbia, South Carolina, Okinawa, Japan and South Korea. In a movie theater there wasn't even an actual flag - just a projection of one on the screen. I remember a buddy on Fort Sill, Oklahoma one summer evening in '97 giving me a beleaguered look when he realized he had to stand up before watching Inventing the Abbotts. We were both drunk, and my friend even fell asleep during the movie, snoring so loudly that I had to wake him to make him stop.

Kaepernick probably resents the fact that his announced motivation has been overshadowed by the usual useless controversy about his First Amendment right of free speech. If pressed, what opinion would his defenders give about his protest? Would they express an opinion at all, or would they go on hiding behind the First Amendment? Freedom of speech doesn't exonerate one from speaking.

This is nothing but political correctness, which, as critic Robert Brustein once put it, is "freedom from speech." Arguing that Kaepernick's protest is purely a matter of free speech does several things to the substance of his gesture. The first thing it does is effectively neutralize it: instead of Kaepernick's solidarity with victims of racism in America, another front of the Black Lives Matter movement, taking center stage and getting all the attention, the issue of free speech takes precedence and obscures the meaning of the speech itself. It also insulates people from charges of racism. What they don't seem to understand is that using the old Voltaire line "I may not agree with what you say but I will defend to the death your right to say it" announces their disagreement with the substance of the speech while silencing further argument. And one more thing that it does is cheapen the importance of speech altogether, which is always a problem in a liberal democracy. In a totalitarian state, the people are told to shut up, but in a liberal democacy they are told to talk all they want because whatever they have to say is of no consequence.

And there is even more to it than that. In his invaluable essay, "On Bullshit," Harry Frankfurt argues: "Bullshit is unavoidable whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about. Thus the production of bullshit is stimulated whenever a person's obligations or opportunities to speak about some topic are more excessive than his knowledge of the facts that are relevant to that topic. This discrepancy is common in public life, where people are frequently impelled whether by their own propensities or by the demands of others to speak extensively about matters of which they are to some degree ignorant. Closely related instances arise from the widespread conviction that it is the responsibility of a citizen in a democracy to have opinions about everything, or at least everything that pertains to the conduct of his country's affairs. The lack of any significant connection between a person's opinions and his apprehension of reality will be even more severe, needless to say, for someone who believes it his responsibility, as a conscientious moral agent, to evaluate events and conditions in all parts of the world."

Unlike men and women in the military who are obliged to stand at attention and salute the flag, for civilians it is a matter of personal delicacy what they do during the national anthem. They aren't obliged to stand. They can remain seated (which is what Kaepernick did at first, before deciding to take a knee), and endure the disfavor of everyone around them. I am amused when I see some of the fans clumsily saluting the flag, which is a duty reserved for people serving in the military.

When I was in the Navy and the Army (in that order, believe it or not) if I was on a military outpost in uniform and a flag was being raised in the morning, I would hear a warning over a loudspeaker called a "tattoo." It is a signal to anyone standing outdoors to either face the direction of the flagpole, come to attention when "reveille" was played and salute the flag, or else I would use the tattoo as an excuse to duck indoors to spare myself the bother.

Honoring the flag is an obligation for people in uniform. Kaepernick isn't dishonoring it, as his vocal critics believe; he is simply declining to honor it. He is entitled to his beliefs. After everything we've gone through as a nation in the past few years, he probably feels the same thing when the announcer says, "Ladies and gentlemen, please stand for our national anthem," that I feel when a speaker announces, "Let us pray." Since I'm not a believer, what the hell am I supposed to do? I definitely can't take a knee.

Many people saw his protest as a show of disrespect for the flag and for American servicemen and women and reacted in anger. When I expressed my own opinion of Kaepernick to my friends on Facebook, pointing out that good judgement was something that he neglected to learn in college all the while he was concentrating on throwing footballs to someone who could catch them, they made a point of defending the quarterback's right to free speech. This is what always happens when a protest, like the Black Lives Matter movement, degenerates into a free speech debate. Even when a Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsberg, chimed in on the subject, calling Kaepernick's actions "dumb," "ridiculous," "offensive," and "arrogant," social media erupted in harsh attacks on her. Probably amazed at the shitstorm her words elicited, Ginsberg has since walked them back, mollifying the same people who had cheered her the last time she shot her mouth off, dismissing Donald Trump a few weeks before. Her critics were merely citing the First Amendment, somehow forgetting that the Justice's job is to remind people of their Constitutional rights.

My remarks about Kaepernick's protest - and Justice Ginsberg's - were a response to the protest itself, the form in which Kaepernick chose to express his protest. I didn't say anything about depriving him of his right to make the protest. So why is everyone so vehemently (and so safely) citing the man's First Amendment right in response to everyone who disagrees with the manner - not the substance - of his protest? Why was Kaepernick's freedom to speak, by taking a knee, worthy of merit and mine (and Justice Gibsberg's) was not?

When I first learned of it, I thought about the reason - the real reason, not the avowed reason - for Kaepernick's distaste for having to stand up before every game. I thought about all the times I, too, had to stand up in movie theaters on military posts throughout my life, from when I was a boy into middle age before I left the Army at 42, in Albany, Georgia, Columbia, South Carolina, Okinawa, Japan and South Korea. In a movie theater there wasn't even an actual flag - just a projection of one on the screen. I remember a buddy on Fort Sill, Oklahoma one summer evening in '97 giving me a beleaguered look when he realized he had to stand up before watching Inventing the Abbotts. We were both drunk, and my friend even fell asleep during the movie, snoring so loudly that I had to wake him to make him stop.

Kaepernick probably resents the fact that his announced motivation has been overshadowed by the usual useless controversy about his First Amendment right of free speech. If pressed, what opinion would his defenders give about his protest? Would they express an opinion at all, or would they go on hiding behind the First Amendment? Freedom of speech doesn't exonerate one from speaking.

This is nothing but political correctness, which, as critic Robert Brustein once put it, is "freedom from speech." Arguing that Kaepernick's protest is purely a matter of free speech does several things to the substance of his gesture. The first thing it does is effectively neutralize it: instead of Kaepernick's solidarity with victims of racism in America, another front of the Black Lives Matter movement, taking center stage and getting all the attention, the issue of free speech takes precedence and obscures the meaning of the speech itself. It also insulates people from charges of racism. What they don't seem to understand is that using the old Voltaire line "I may not agree with what you say but I will defend to the death your right to say it" announces their disagreement with the substance of the speech while silencing further argument. And one more thing that it does is cheapen the importance of speech altogether, which is always a problem in a liberal democracy. In a totalitarian state, the people are told to shut up, but in a liberal democacy they are told to talk all they want because whatever they have to say is of no consequence.

And there is even more to it than that. In his invaluable essay, "On Bullshit," Harry Frankfurt argues: "Bullshit is unavoidable whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about. Thus the production of bullshit is stimulated whenever a person's obligations or opportunities to speak about some topic are more excessive than his knowledge of the facts that are relevant to that topic. This discrepancy is common in public life, where people are frequently impelled whether by their own propensities or by the demands of others to speak extensively about matters of which they are to some degree ignorant. Closely related instances arise from the widespread conviction that it is the responsibility of a citizen in a democracy to have opinions about everything, or at least everything that pertains to the conduct of his country's affairs. The lack of any significant connection between a person's opinions and his apprehension of reality will be even more severe, needless to say, for someone who believes it his responsibility, as a conscientious moral agent, to evaluate events and conditions in all parts of the world."

Unlike men and women in the military who are obliged to stand at attention and salute the flag, for civilians it is a matter of personal delicacy what they do during the national anthem. They aren't obliged to stand. They can remain seated (which is what Kaepernick did at first, before deciding to take a knee), and endure the disfavor of everyone around them. I am amused when I see some of the fans clumsily saluting the flag, which is a duty reserved for people serving in the military.

When I was in the Navy and the Army (in that order, believe it or not) if I was on a military outpost in uniform and a flag was being raised in the morning, I would hear a warning over a loudspeaker called a "tattoo." It is a signal to anyone standing outdoors to either face the direction of the flagpole, come to attention when "reveille" was played and salute the flag, or else I would use the tattoo as an excuse to duck indoors to spare myself the bother.

Honoring the flag is an obligation for people in uniform. Kaepernick isn't dishonoring it, as his vocal critics believe; he is simply declining to honor it. He is entitled to his beliefs. After everything we've gone through as a nation in the past few years, he probably feels the same thing when the announcer says, "Ladies and gentlemen, please stand for our national anthem," that I feel when a speaker announces, "Let us pray." Since I'm not a believer, what the hell am I supposed to do? I definitely can't take a knee.

Thursday, October 20, 2016

A Junkie's Lament

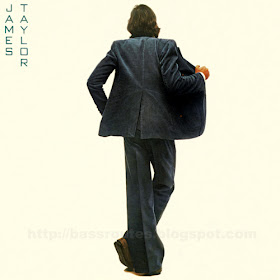

James Taylor is one of the most enduringly popular recording artists of the past fifty years. Although a product of the Sixties, few people would think of associating him with the drug culture of the time, and even fewer people remember him as a serious addict, or "junkie." Yet Taylor claims that he fought an addiction to heroin for twenty years.

As he told The Rolling Stone in 2015, "I had taken my first opiate in 1966. Joel 'Bishop' O'Brien, the drummer in the Flying Machine, was an addict. I spent a lot of time at his apartment, so it was just a matter of time before I tried heroin. I was pretty much born to shoot dope - it was the key to my lock, so I really was gone for the next 20 years."

Taylor's 1976 album, In the Pocket is one of his richest, despite the fact that only one of the twelve songs it contains, "Shower the People," became a hit. Like many other of his recorded songs, the rest of the album has remained virtually unknown since its first release. Two songs from the album, which I'm somewhat ashamed to say I heard for the first time last year, have since acquired a special value for me. As a substance abuser myself (alcohol), I found myself identifying strongly with the words to Taylor's songs "Golden Moments" and "A Junkie's Lament," both of which paint vivid pictures of the highs and lows of addiction.

The song "Golden Moments" is disarmingly lovely. It's subject is bliss, but Taylor's lyrics to the song give one clues about the origin of the bliss:

Now if all my golden moments could be rolled into one,

They would shine just like the sun for a summer day.

And after it was over, we could have it back again,

With credit to the editor for striking out the rain - very clean.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna bring me down.

No one's gonna stop me now.

Now I gathered up my sorrows and I sold them all for gold,

And I gathered up the gold and I threw it all away.

It all went for a good time and a song - come on.

The laughter was like music, it did float my soul along - for a while.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna reach me here.

No one's gonna know I'm gone.

You may think I must be crazy, and I guess you must be right,

But I know the way I feel today is out of sight.

I do not trust my senses to remember your name.

Without corrective lenses, things are never quite the same - anyway.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna bring me down.

No one's gonna stop me now.

No one's gonna reach me here.

No one's gonna know I'm gone.

What else could Taylor be singing about, in such diaphanously dreamy music, but getting high? He wants to escape, to be where no one can find him, where no one can stop him (or criticize him). What better ticket to oblivion than heroin? Like all drugs with which people self-medicate, it is a disease but also its cure. Escape can only be temporary, but while we are in its thrall, nothing can touch us. The world recedes to a faint murmur, a distant commotion on the horizon.

Taylor was honest enough with himself to celebrate his highs, and to give us a vivid impression of what they were like - but he didn't fail to describe, in telling language, his lows. If addiction were nothing but a constant high, no one would want to be rid of it. But unless the highs are evened out with occasional lows, a drying out, being strung out, the addiction would lead to inevitable overdose and death.

The other song from Taylor's album In the Pocket that, ironically, is on Side B,(1) that relates to us the other side of addiction, is called "A Junkie's Lament." It is the perfect companion piece to "Golden Moments."

While never having tried heroin, I know where Taylor is coming from in the tellingly direct words to "A Junkie's Lament":

Rick's been kicking the gong, lickety-split, didn't take too long.

A junkie's sick, a monkey's strong, that's what's wrong.

Well, I guess he's been messing around downtown,

so sad to see the man losing ground.

Winding down behind closed doors

On all fours.

Mama, don't you call him my name.

He can't hear you any more.

Even if he seems the same

to you, that's a stranger

to your door.

Go on, ask him what's he come here for.

Oh my God, a monkey can move a man.

Send him to hell and home again.

An empty hand in the afternoon,

shooting for the moon.

It's halfway sick and it's halfway stoned.

He'd sure like to kick but he's too far gone.

They wind him down with the methadone.

He's all on his own.

But baby, don't you throw your love away.

I hate to seem unkind.

It's only that I understand the man

that the monkey can leave behind.

I used to think he was a friend of mine.

La la la la la la la la . . .

As Taylor explained to The Rolling Stone:

"I've got a lot of recovery songs. This one's ["A Junkie's Lament"] a warning not to think of a junkie as a complete functioning human being. Heroin should've killed me about five times, but it never did....People take drugs to be in control. They want to short-circuit any risk that they might take in life, any uncertainty, any anxiety. They just want to find the chemical route, to just push the button that gets the final result."

As I said, I didn't become acquainted with these two songs until the summer of 2015, during my last bad bender. Having been a habitual drinker since the death of my father in 1988, with occasional respites, all the way up until 2004, when I began to routinely experience serious withdrawals (without knowing exactly what they were at first), it was late that year that I discovered a dangerous solution to my withdrawals: the hair of the dog that bit me - i.e., continuous drinking. Eventually, this discovery contributed to my losing two jobs, which forced me to move in with my sister, abandoning an apartment full of furniture to fly from Des Moines, Iowa all the way to Anchorage, Alaska. Since then, however, I have interspersed extended stretches of sobriety with occasional benders. I never quite know what provokes them. They arrive out of the blue after sometimes months of abstention.

What I have learned is the same thing that Taylor evidently learned a much harder way: what every addict must face before he goes too far is the choice between life or death. He cannot go on using or he will end up dead. It's always the same choice: get clean and live or go on using and die. Choosing life has its obvious perks, but how enticing those beautiful dying notes from "Golden Moments" sometimes seem.

In the treatment of bi-polar disorder, physicians do us no favors by informing us that depression is nothing but a chemical imbalance that can be corrected with prescription drugs. What is happiness, then, but a similar treatable chemical imbalance? Having taken Prozac for awhile in 2006, during a long sober stretch, after about a month of low doses I suddenly felt as if someone had turned on all the lights. I was awake for the first time in more than a year. Unfortunately, the drug also made me more confrontational and argumentative, unsatisfied with my life. And within weeks I was drinking again. For the untreated, self-medicating user, withdrawals (depression) is the price he pays for getting high (happiness). What he must figure out - "all on his own" - is whether or not it is worth it.

(1) In actuality, the track listing for In the Pocket places "A Junkie's Lament" on Side A, Track 2 and "Golden Moments" on Side B, Track 6. Significantly, the album closes with Taylor's evocation of opiate bliss.

As he told The Rolling Stone in 2015, "I had taken my first opiate in 1966. Joel 'Bishop' O'Brien, the drummer in the Flying Machine, was an addict. I spent a lot of time at his apartment, so it was just a matter of time before I tried heroin. I was pretty much born to shoot dope - it was the key to my lock, so I really was gone for the next 20 years."

Taylor's 1976 album, In the Pocket is one of his richest, despite the fact that only one of the twelve songs it contains, "Shower the People," became a hit. Like many other of his recorded songs, the rest of the album has remained virtually unknown since its first release. Two songs from the album, which I'm somewhat ashamed to say I heard for the first time last year, have since acquired a special value for me. As a substance abuser myself (alcohol), I found myself identifying strongly with the words to Taylor's songs "Golden Moments" and "A Junkie's Lament," both of which paint vivid pictures of the highs and lows of addiction.

The song "Golden Moments" is disarmingly lovely. It's subject is bliss, but Taylor's lyrics to the song give one clues about the origin of the bliss:

Now if all my golden moments could be rolled into one,

They would shine just like the sun for a summer day.

And after it was over, we could have it back again,

With credit to the editor for striking out the rain - very clean.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna bring me down.

No one's gonna stop me now.

Now I gathered up my sorrows and I sold them all for gold,

And I gathered up the gold and I threw it all away.

It all went for a good time and a song - come on.

The laughter was like music, it did float my soul along - for a while.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna reach me here.

No one's gonna know I'm gone.

You may think I must be crazy, and I guess you must be right,

But I know the way I feel today is out of sight.

I do not trust my senses to remember your name.

Without corrective lenses, things are never quite the same - anyway.

And all it really needed was the proper point of view.

No one's gonna bring me down.

No one's gonna stop me now.

No one's gonna reach me here.

No one's gonna know I'm gone.

What else could Taylor be singing about, in such diaphanously dreamy music, but getting high? He wants to escape, to be where no one can find him, where no one can stop him (or criticize him). What better ticket to oblivion than heroin? Like all drugs with which people self-medicate, it is a disease but also its cure. Escape can only be temporary, but while we are in its thrall, nothing can touch us. The world recedes to a faint murmur, a distant commotion on the horizon.

Taylor was honest enough with himself to celebrate his highs, and to give us a vivid impression of what they were like - but he didn't fail to describe, in telling language, his lows. If addiction were nothing but a constant high, no one would want to be rid of it. But unless the highs are evened out with occasional lows, a drying out, being strung out, the addiction would lead to inevitable overdose and death.

The other song from Taylor's album In the Pocket that, ironically, is on Side B,(1) that relates to us the other side of addiction, is called "A Junkie's Lament." It is the perfect companion piece to "Golden Moments."

While never having tried heroin, I know where Taylor is coming from in the tellingly direct words to "A Junkie's Lament":

Rick's been kicking the gong, lickety-split, didn't take too long.

A junkie's sick, a monkey's strong, that's what's wrong.

Well, I guess he's been messing around downtown,

so sad to see the man losing ground.

Winding down behind closed doors

On all fours.

Mama, don't you call him my name.

He can't hear you any more.

Even if he seems the same

to you, that's a stranger

to your door.

Go on, ask him what's he come here for.

Oh my God, a monkey can move a man.

Send him to hell and home again.

An empty hand in the afternoon,

shooting for the moon.

It's halfway sick and it's halfway stoned.

He'd sure like to kick but he's too far gone.

They wind him down with the methadone.

He's all on his own.

But baby, don't you throw your love away.

I hate to seem unkind.

It's only that I understand the man

that the monkey can leave behind.

I used to think he was a friend of mine.

La la la la la la la la . . .

As Taylor explained to The Rolling Stone:

"I've got a lot of recovery songs. This one's ["A Junkie's Lament"] a warning not to think of a junkie as a complete functioning human being. Heroin should've killed me about five times, but it never did....People take drugs to be in control. They want to short-circuit any risk that they might take in life, any uncertainty, any anxiety. They just want to find the chemical route, to just push the button that gets the final result."

As I said, I didn't become acquainted with these two songs until the summer of 2015, during my last bad bender. Having been a habitual drinker since the death of my father in 1988, with occasional respites, all the way up until 2004, when I began to routinely experience serious withdrawals (without knowing exactly what they were at first), it was late that year that I discovered a dangerous solution to my withdrawals: the hair of the dog that bit me - i.e., continuous drinking. Eventually, this discovery contributed to my losing two jobs, which forced me to move in with my sister, abandoning an apartment full of furniture to fly from Des Moines, Iowa all the way to Anchorage, Alaska. Since then, however, I have interspersed extended stretches of sobriety with occasional benders. I never quite know what provokes them. They arrive out of the blue after sometimes months of abstention.

What I have learned is the same thing that Taylor evidently learned a much harder way: what every addict must face before he goes too far is the choice between life or death. He cannot go on using or he will end up dead. It's always the same choice: get clean and live or go on using and die. Choosing life has its obvious perks, but how enticing those beautiful dying notes from "Golden Moments" sometimes seem.